Traducido por Natalia Cuadrado y Isabel Ferrer (from the original in English Dominance—Making Sense of the Nonsense).

El tema de la dominancia se nos ha ido de las manos. Solo hay una cosa más absurda e inútil que molestarse en demostrar que la dominancia existe, y es el intento de demostrar que la dominancia no existe. Yo voy a cometer el primero de estos actos inútiles.

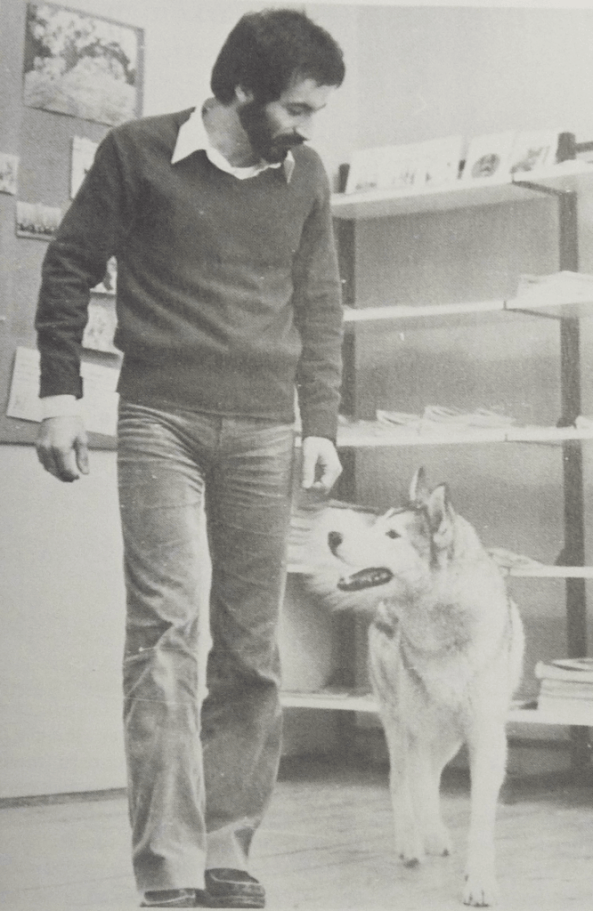

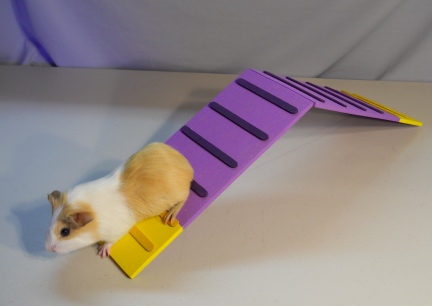

Las posibles combinaciones de comportamentos agresivos, temerosos, dominates y sumisos en los caninos sociales (de “Dog Langauge” de Roger Abrantes, ilustración protegida por copyright de Alice Rasmussen).

Dominancia, en el lenguaje corriente, significa «poder e influencia sobre otros». Quiere decir supremacía, superioridad, predominancia, dominio, poder, autoridad, mando, control. Tiene tantos significados y connotaciones que es difícil saber cómo utilizar la palabra en tanto término científico preciso aplicado a las ciencias del comportamiento. Además, los científicos que la utilizan (así como los que la repudian) no se han esforzado demasiado por definirla de una manera exacta, lo que ha contribuido a la actual confusión, discusiones sin sentido, desacuerdos y afirmaciones absurdas.

Es mi intención poner remedio a esto, primero demostrando que la dominancia sí existe, y después estableciendo que hace referencia a un mismo tipo de comportamiento, independientemente de la especie en cuestión. A continuación, daré una definición precisa, pragmática y verificable del término, que será compatible con la teoría de la evolución y nuestros conocimientos sobre la biología. Finalmente, expondré que, si bien es cierto que una buena relación (beneficiosa y estable) no se fundamenta en continuas demostraciones de dominancia/sumisión por parte de los mismos individuos ante los mismos individuos, eso tampoco implica que la dominancia no exista en perros (y en cualquier otra especie). Negar la existencia de la dominancia en perros se ha convertido en una argumentación muy difundida para afirmar que no debemos construir una relación con nuestros perros basada en la dominancia.

Es absurdo sostener que la dominancia no existe cuando tenemos tantas palabras que describen todo lo relacionado con ella. Si no existiera, no tendríamos siquiera una palabra que hiciera referencia a ella. El hecho de que el término exista quiere decir que la hemos visto a nuestro alrededor. Podemos afirmar que la hemos observado y que el término (1) hace referencia únicamente a determinadas relaciones humanas, o que (2) se refiere a determinadas relaciones tanto entre humanos como entre otras especies animales. La segunda opción parece más atractiva, considerando el hecho de que es muy improbable que una condición en particular solo se dé en una única especie. Eso entraría en conflicto con todo lo que sabemos acerca del parentesco entre las especies y su evolución.

Sin embargo, no es descabellado sostener que el término no es aplicable para describir el comportamiento de determinadas especies. Al contrario, dos especies que han evolucionado desde un antepasado común hace billones de años han desarrollado características propias y difieren del antepasado común y entre ellas. De igual modo, especies muy cercanas, que se separaron hace sólo unos miles de años de un antepasado común, pueden presentar características similares o iguales entre ellas y respecto al antepasado común. Algunas especies comparten muchos atributos en común relativos al fenotipo, el genotipo y/o la conducta; otras comparten menos, y otras ninguno. Todo depende de su antepasado común y de su adaptación al entorno.

Los seres humanos y los chimpancés (Homo sapiens y Pan troglodytes) se han separado de su antepasado común hace seis millones de años, de manera que podemos esperar que existan más diferencias entre ellos que entre los perros y los lobos (Canis lupus y Canis lupus familiaris), que se separaron de su antepasado común hace sólo unos 15-20 mil años (y de ninguna manera hace más de 100.000 años). Hay más diferencias en el ADN del hombre y el chimpancé que en el del perro y el lobo (que son prácticamente idénticos salvo por unas pocas mutaciones). Los hombres no pueden reproducirse con chimpancés, mientras que los lobos y los perros pueden tener descendencia fértil. Los hombres y los chimpancés son dos especies completamente diferentes. Los lobos y los perros son dos subespecies de la misma especie.

Teniendo en cuenta estos hechos, podemos esperar que los lobos y los perros compartan un gran número de similitudes, cosa que así es, no solo físicas sino también conductuales. Cualquier lego en la materia lo afirmaría. Sus similitudes a uno u otro nivel son lo que les permite cruzarse entre sí, producir descendencia fértil y comunicarse. Nadie ha cuestionado que los lobos y los perros presentan un amplio repertorio de comportamientos de comunicación en común, y con toda la razón, ya que múltiples estudios confirman que son capaces de comunicarse perfectamente. Sus expresiones faciales y posturas corporales son muy parecidas (exceptuando ciertas razas de perros), con pequeñas diferencias que son menores entre sí que las diferencias culturales que podemos encontrar entre poblaciones de seres humanos geográficamente alejadas.

En una manada estable, los lobos suelen presentar una conducta dominante y sumisa y rara vez una conducta temerosa y agresiva.

Si los lobos y los perros pueden comunicarse, podemos concluir que los elementos básicos y determinantes de su lenguaje deben ser los mismos. Esto quiere decir que aunque han evolucionado en ambientes aparentemente diferentes, mantienen los elementos más anclados de sus características genotípicas. Esto puede ser por tres motivos: (1) los genotipos compartidos son vitales para el organismo, (2) los entornos en que viven al fin y al cabo no son tan diferentes, (3) la evolución necesita más tiempo y condiciones más selectivas (debido a que actúa sobre los fenotipos) antes de que los genotipos cambien de manera radical. La primera razón significa que hay más maneras de no sobrevivir que de sobrevivir, o en otras palabras, que la evolución necesita tiempo para desarrollar formas de vida diferentes y viables; la segunda razón significa que aunque los lobos y los perros (mascotas) viven actualmente en entornos muy diferentes, el fenómeno es todavía reciente. Solo hace unos cien años que los perros están plenamente humanizados. Hasta entonces, eran nuestros compañeros, nuestros animales domésticos, pero todavía tenían un elevado grado de libertad y los factores selectivos exitosos eran básicamente los mismos de siempre. No eran todavía mascotas y la cría no estaba totalmente (o casi totalmente) controlada por la selección humana. La tercera razón significa que quizás un día (de aquí a un millón de años o más), tendremos dos especies totalmente diferentes, perros y lobos. Para entonces, no podrán cruzarse, no producirán descendencia fértil y presentarán características completamente diferentes. Habrán cambiado el nombre, a quizá llamarse Canis civicus o Canis homunculus. ¡Sin embargo, todavía no hemos llegado a eso!

Según las últimas tendencias, el «comportamiento dominante» no existe en el perro, lo que plantea algunos problemas serios. Hay dos maneras de defender esta idea. Una es desechar el concepto «comportamiento dominante» por completo, lo que es absurdo, por las razones que hemos visto antes: el término existe, sabemos más o menos lo que significa y podemos utilizarlo en una conversación con cierto sentido. Por lo tanto, debe referirse a un tipo de comportamiento que hemos observado. Otra argumentación es afirmar que los lobos y los perros son completamente diferentes y, por lo tanto, incluso aunque podamos aplicar el término para explicar el comportamiento del lobo, no podemos utilizarlo para describir el comportamiento del perro. Si fueran completamente diferentes, la argumentación sería válida, pero no lo son, como ya hemos visto. Por el contrario, son muy parecidos.

Una tercera alternativa es construir una teoría totalmente nueva para explicar cómo dos especies tan cercanas como el lobo y el perro (de hecho, subespecies) pueden haber desarrollado en un periodo de tiempo tan breve (miles de años) tantas características radicalmente distintas en un aspecto, pero no en otros. Esto nos llevaría a llevar a cabo una extensa revisión de todos nuestros conocimientos biológicos, lo que tendría implicaciones que van más allá de los lobos y los perros, y ésa es una alternativa que considero poco realista.

Híbrido de perro-lobo (Imagen via Wikipedia).

Una aproximación mucho más atractiva, en mi opinión, es analizar los conceptos que utilizamos y definirlos bien. Así podremos emplearlos con más sentido cuando abordemos las diferentes especies, sin incurrir en incompatibilidades con el mundo científico.

Tener una definición apropiada de «comportamiento dominante» es importante, porque el comportamiento que implica es vital para la supervivencia del individuo, como veremos.

Me parece que es un enfoque pobre desechar la existencia de hechos que están detrás de un término sólo porque el término está mal definido, por no decir que es políticamente incorrecto (lo que significa que no se ajusta a nuestros objetivos inmediatos). El comportamiento dominante existe, simplemente está mal definido (cuando se define). Muchas discusiones relacionadas con este tema no tienen sentido porque ninguna de las partes sabe exactamente de qué habla la otra. Sin embargo, no es necesario tirarlo todo por la borda. Por lo tanto, propongo definiciones precisas tanto del comportamiento dominante como del resto de términos que necesitamos para entenderlo: qué es, qué no es, cómo ha evolucionado y cómo funciona.

El comportamiento dominante es un comportamiento cuantitativo y cuantificable manifestado por un individuo con el objetivo de conseguir o conservar el acceso temporal a un recurso en particular, en una situación en concreto, ante un oponente concreto, sin que ninguna de las partes resulte herida. Si cualquiera de las partes resulta herida, se trata de un comportamiento agresivo, no dominante. Sus características cuantitativas varían desde un ligero aplomo hasta una clara afirmación de la autoridad.

El comportamiento dominante es contextual, individual y está relacionado con los recursos. Un individuo que manifiesta un comportamiento dominante en una situación específica no necesariamente lo va a mostrar en otra ocasión ante otro individuo, o ante el mismo individuo en una situación distinta.

Los recursos son lo que los organismos perciben como necesidades vitales; por ejemplo, la comida, una pareja reproductiva, o parte del territorio. La percepción de lo que un animal puede considerar un recurso depende de la especie y el individuo.

La agresividad (el comportamiento agresivo) es el comportamiento encaminado a eliminar la competencia, mientras que la dominancia, o la agresividad social, es un comportamiento dirigido a eliminar la competencia de un compañero.

Los compañeros son dos o más animales que conviven estrechamente y dependen el uno del otro para su supervivencia. Los extraños son dos o más animales que no conviven estrechamente y no dependen el uno del otro para sobrevivir.

El comportamiento dominante es especialmente importante para animales sociales que necesitan cohabitar y cooperar para sobrevivir. Por lo tanto, se desarrolló una estrategia social con la función de tratar la competencia entre compañeros con unas desventajas mínimas.

Los animales manifiestan comportamientos dominantes con varias señales: visuales, auditivas, olfativas y/o táctiles.

Mientras que el miedo (una conducta temerosa) es un comportamiento dirigido a eliminar una amenaza inminente, el comportamiento de sumisión, o el miedo social, es un comportamiento orientado a eliminar una amenaza social de un compañero; es decir, la pérdida temporal de un recurso sin que nadie se haga daño.

Una amenaza es todo aquello que puede herir, provocar dolor o lesiones, o disminuir las posibilidades de un individuo de sobrevivir. Una amenaza social es cualquier cosa que pueda producir la pérdida temporal de un recurso y que provoque un comportamiento de sumisión o una huida sin que el individuo sumiso termine lesionado.

Los animales manifiestan el comportamiento de sumisión mediante diferentes señales: visuales, auditivas, olfativas y/o táctiles.

Un comportamiento dominante o sumiso persistente de los mismos individuos puede dar lugar o no a una jerarquía temporal con determinadas configuraciones según la especie, la organización social y las circunstancias del entorno. En los grupos estables que ocupan un territorio definido, las jerarquías temporales se desarrollan más fácilmente. En los grupos inestables, en condiciones del entorno cambiantes, o en territorios no definidos o no establecidos, las jerarquías no se desarrollan. Las jerarquías, o más bien las estrategias implicadas, son Estrategias Estables Evolutivas (EEE), que son siempre ligeramente inestables, que oscilan constantemente alrededor de un valor óptimo según el número de individuos de cada grupo y las estrategias individuales que cada uno adopta en un momento determinado, Las jerarquías no son necesariamente lineales, aunque en grupos pequeños y con el tiempo, las jerarquías no lineales parecen tender a ser más lineales.

Algunos individuos tienden a mostrar comportamientos dominantes y otros a mostrar comportamientos sumisos. Eso puede depender de su configuración genética, su aprendizaje a una edad temprana, su historial, etc. Eso no significa que lo determine un solo factor, sino que se trata de una compleja mezcla. Llamémoslo tendencia natural, lo que no quiere decir que no sea modificable. Es un hecho que algunos individuos son más autoritarios que otros, mientras que otros son más condescendientes, por muchas razones. No estamos diciendo que esto sea bueno o malo, simplemente exponemos un hecho; que sea bueno o malo —no en un sentido moral— más bien significa que es más o menos ventajoso según el contexto. En los encuentros cara a cara, en condiciones de igualdad, hay más probabilidades de que los individuos adopten la estrategia con la que se encuentran más cómodos, manteniendo por lo tanto su historial de básicamente dominantes o básicamente sumisos.

Cuando están en un grupo de mayor tamaño, tendrán la misma tendencia de desempeñar los roles con los que se sienten más cómodos. Esto puede cambiar, sin embargo, debido a la estructura formada accidentalmente del grupo. Imagina un grupo con varios individuos con una mayor tendencia a tener comportamientos sumisos que dominantes, y con sólo unos pocos individuos con la tendencia opuesta. En una situación así, un individuo por naturaleza sumiso tendrá más posibilidades de acceder a un recurso y tener éxito mostrando un comportamiento más dominante. El éxito genera éxito, y poco a poco, este individuo, que en otras condiciones sería predominantemente sumiso, se encuentra con que es principalmente dominante. Si la situación permite al individuo cambiar su estrategia preferente, los demás también tendrán las mismas oportunidades. El número de individuos dominantes aumentará, pero el número de individuos dominantes que puede sostener un grupo no es ilimitado, porque en un momento dado será más ventajoso asumir el papel de sumiso, según los costes y los beneficios.

Por lo tanto, el número de individuos dominantes y sumisos no sólo depende de la tendencia natural del individuo, sino también de la configuración de los grupos y sus características. Si compensa tener un papel dominante o sumiso en el fondo es algo que depende de los costes y beneficios y del número de individuos que adoptan una estrategia en particular.

Entender las relaciones entre comportamientos dominantes y sumisos como una EEE (Estrategia Estable Evolutiva) abre perspectivas de lo más emocionantes, que pueden ayudar a explicar los comportamientos adoptados por un individuo determinado en un momento dado. Un individuo sumiso aprenderá a desempeñar el papel de sumiso ante otros individuos más dominantes y el de dominante ante otros más sumisos. Eso significa que ningún individuo es en principio siempre dominante o siempre sumiso; todo depende del contrario y, por supuesto, del valor de los beneficios potenciales y los costes estimados.

Por consiguiente, las jerarquías (cuando existen) siempre serán ligeramente inestables según las estrategias adoptadas por los individuos que forman el grupo. Las jerarquías no son necesariamente lineales y sólo se dan en pequeños grupos o subgrupos.

En opinión de este autor, el error que hemos cometido hasta ahora es considerar la dominancia y la sumisión como algo más o menos estático. No hemos tenido en cuenta que estas características, como los fenotipos y todos los demás rasgos, están constantemente bajo el escrutinio y la presión de la selección natural. Son adaptativas, muy variables y altamente cuantitativas y cuantificables.

Como tal, la dominancia y la sumisión son rasgos dinámicos que dependen de diversas variables, visión que es compatible con el desarrollo del comportamiento a un nivel individual, las funciones genéticas, la influencia del aprendizaje y, cómo no, la teoría de la evolución.

La dominancia y la sumisión son mecanismos maravillosos desde un punto de vista evolutivo. Es lo que permite a los animales (sociales) vivir juntos, sobrevivir hasta que se hayan reproducido y transmitir sus genes (dominantes y sumisos) a la siguiente generación. Sin estos mecanismos, no tendríamos animales sociales como los seres humanos, los chimpancés, los lobos y los perros, entre muchos otros.

Si un animal resolviera todos los conflictos intergrupales con comportamientos agresivos y temerosos, estaría agotado cuando se viera obligado a buscar la comida, una pareja reproductiva, un lugar seguro para descansar o cuidar de su progenie (y todo ello disminuiría las oportunidades de sobrevivir tanto de él como de sus genes). Por consiguiente, se originó y desarrolló la estrategia del compañero y el extraño. Es imposible luchar contra todos todo el tiempo, de manera que con los compañeros se utilizan mecanismos que consumen poca energía en las confrontaciones.

Los comportamientos dominantes y sumisos controlan asimismo la densidad de población, ya que dependen del reconocimiento individual. El número de reconocimientos individuales que es capaz de realizar un animal debe tener un límite. Si este limite es muy alto, el reconocimiento se vuelve ineficiente, inactivando la estrategia compañero/extraño; en ese caso, las expresiones de miedo/agresividad sustituirán a los comportamientos de sumisión/dominancia.

La estrategia de sumisión es sabia. En lugar de enzarzarse en vano en una lucha desesperada, puede resultar mucho más provechoso esperar. Recurriendo a un comportamiento pacifico y sumiso, los subordinados a menudo pueden seguir los pasos de los dominantes y aprovechar oportunidades que les dan acceso a recursos vitales. Mostrando sumisión, gozan además de las ventajas de pertenecer a un grupo, en especial la defensa ante los rivales.

Las jerarquías funcionan porque el subordinado normalmente se aparta, mostrando un típico comportamiento apaciguador, sin signos aparentes de miedo. Por lo tanto, el dominante puede sencillamente desplazar al sumiso cuando está comiendo o cuando desea un espacio. Las jerarquías en la naturaleza a menudo son muy sutiles, difíciles de descubrir por el observador. El motivo de esta sutileza es la razón de ser de la propia dominancia-sumisión: el animal subordinado suele evitar los encontronazos y al dominante tampoco le entusiasman las escaramuzas.

Pelear implica cierto riesgo y puede dar lugar a graves lesiones, o incluso a la muerte. La evolución, por consiguiente, tiende a favorecer y desarrollar mecanismos que limitan la intensidad de los comportamientos agresivos. Muchas especies tienen claras señales que expresan la aceptación de la derrota, lo que pone fin a las peleas antes de que se produzcan lesiones.

Aprender a reconocer las señales-estímulos es la tarea más importante para las crías nada más nacer. Les salva la vida. La lección más importante que aprende un joven social después de aprender las señales–estímulos fundamentales para mantenerse con vida es la capacidad de transigir. Mantiene la salud de la vida social del grupo. La selección natural lo ha demostrado, favoreciendo a los individuos que han desarrollado comportamientos que les permiten permanecer juntos. Otros animales, los depredadores solitarios, no necesitan estos rasgos sociales. Estos organismos encuentran otras maneras de mantener su metabolismo y reproducción.

Aprender a ser social significa aprender a transigir. Los animales sociales pasan mucho tiempo juntos y los conflictos son inevitables. Tiene su lógica que desarrollen mecanismos con los que responder a las hostilidades. Limitar el comportamiento de agresividad y miedo mediante la inhibición y la ritualización sólo es parcialmente seguro. Cuanto más social es el animal, más obligatorios son los mecanismos eficaces. La agresión inhibida sigue siendo una agresión; es como jugar con fuego un día de viento. Resulta eficaz para animales menos sociales o menos agresivos, pero los animales muy sociales y más agresivos necesitan otros mecanismos.

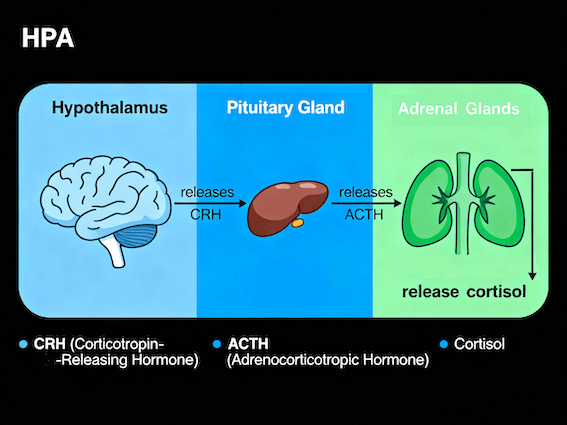

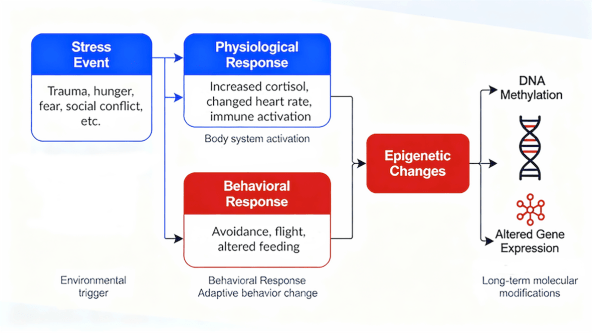

A largo plazo, seria muy peligroso y agotador estar constantemente recurriendo a la agresión y el miedo para resolver problemas triviales. Los animales presentan síntomas de estrés patológico después de un tiempo en que se sienten constantemente amenazados o necesitan atacar constantemente a otros. Esto significa que los depredadores sociales necesitan otros mecanismos aparte de la agresividad y el miedo para resolver animosidades sociales. Tengo la teoría de que los animales sociales, a través de la ontogenia de la agresión y el miedo, desarrollan otros dos comportamientos sociales igual de importantes. Mientras que una agresión significa: «lárgate, muérete, no vuelvas a molestarme», una agresión social significa: «lárgate, pero no demasiado lejos, ni demasiado tiempo». Igualmente, el miedo social dice: «No te molestaré si no me haces daño», mientras que el miedo existencial no permite transigir en nada: «o tú o yo».

La diferencia significativa entre los dos tipos de comportamientos agresivos parece ser la función. La agresión se emplea para tratar con los extraños, y la agresión social se emplea para tratar con los compañeros. En cambio, el miedo y el miedo social son tanto para el trato con los extraños como para el trato con los compañeros. Éstas son diferencias cualitativas que justifican la creación de nuevos términos; de allí que se hable de dominancia y sumisión.

¿Qué significado tiene esto en nuestra manera de entender a nuestros perros y nuestra relación con ellos?

Significa que todos nosotros mostramos comportamientos dominantes (seguridad en uno mismo, afirmación de la autoridad, firmeza, contundencia) y sumisos (inseguridad, aceptación, concesión, capitulación), según diversos factores, por ejemplo: estado de ánimo, posición social, recursos, salud, el oponente en cuestión, y eso se da tanto entre los seres humanos como entre los perros (y los lobos, por supuesto). Esto no tiene nada de malo, excepto cuando presentamos un comportamiento dominante en situaciones en que sería más ventajoso presentar un comportamiento sumiso, y viceversa. A veces podemos ser más dominantes o sumisos, y otras veces menos. Se trata de comportamientos muy cuantitativos y cuantificables, con muchas variantes. No hay una única estrategia correcta. Todo dependerá de la flexibilidad y la estrategia adoptada por los demás.

Por supuesto, nosotros no construimos las relaciones estables y beneficiosas a largo plazo basándolas en los comportamientos dominantes o sumisos. Éstos son comportamientos necesarios para resolver los inevitables conflictos sociales. Construimos las relaciones basándolas en la necesidad de compañía –tanto nosotros como los perros (y los lobos, por supuesto)– para resolver problemas comunes relacionados con la supervivencia y preferentemente con un nivel aceptable de confort. No construimos las relaciones basándolas en las jerarquías, pero éstas existen y desempeñan un papel importante en determinadas circunstancias –tanto para los seres humanos como para los perros (y para los lobos, por supuesto)-, a veces más, a veces menos, a veces nada.

Construimos nuestra (buena) relación particular con nuestros perros basándola en el compañerismo. Los necesitamos porque nos dan una sensación de logro que no parece que consigamos en otra parte. Ellos nos necesitan porque el mundo esta superpoblado, los recursos son limitados y como dueños les proporcionamos comida, protección, cuidados, un lugar seguro y compañía (son animales sociales). ¡Es muy duro ser un perrito y estar solo en este mundo tan grande! A veces, en esta relación, una de las partes recurre a un comportamiento dominante o sumiso y eso no tiene nada de malo siempre y cuando las dos partes no exhiban el mismo comportamiento a la vez. Si ambos muestran comportamiento dominante o sumiso, tienen un problema: habrá un conflicto que se resolverá la mayor parte de las veces sin lesiones (eso es lo maravilloso de la dominancia y la sumisión), o uno de los dos tendrá que dejarse de tonterías e imponer su buen juicio.

Una buena relación con nuestros perros no requiere ningún mecanismo en particular ni misterioso. Ocurre básicamente lo mismo con todas las buenas relaciones, teniendo en cuenta las características especificas de la especie y los individuos implicados. No necesitamos nuevos términos. No necesitamos nuevas teorías para explicarlo. No somos, al fin y al cabo, tan especiales, y tampoco lo son nuestros perros. Estamos todos construidos a partir del mismo concepto y con los mismos ingredientes básicos. Sólo necesitamos buenas definiciones y un enfoque menos emocional y más racional. Utiliza tu corazón para disfrutar de tu perro (y de tu vida) y tu razón para explicarlo (si lo necesitas), y no al revés. Si no te gustan mis definiciones, crea otras que sean mejores (con más ventajas y menos desventajas), pero no malgastes tu tiempo (ni el de nadie) con discusiones sin sentido y reacciones viscerales. La vida es preciosa y cada momento malgastado es un bocado menos del pastel que has devorado sin siquiera darte cuenta.

Así es como yo lo veo y me parece hermoso: ¡que disfrutes de tu pastel!

R—

Related articles

References

- Abrantes, R. 1997. The Evolution of Canine Social Behavior. Wakan Tanka Publishers.

- Coppinger, R. and Coppinger, L. 2001. Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. Scribner.

- Creel, S., and Creel, N. M. 1996. Rank and reproduction in cooperatively breeding African wild dogs: behavioral and endocrine correlates. Behav. Ecol. 8:298-306.

- Darwin, C. 1872. The Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals. John Murray (the original edition).

- Estes, R. D., and Goddard, J. 1967. Prey selection and hunting behavior of the African wild dog. J. Wildl. Manage. 31:52-70.

- Eaton, B. 2011. Dominance in Dogs—Fact or Fiction? Dogwise Publishing.

- Fentress, J. C., Ryon, J., McLeod, P. J., and Havkin, G. Z. 1987. A multi- dimensional approach to agonistic behavior in wolves. In Man and wolf: advances, issues, and problems in captive wolf research. Edited by H. Frank. Dr. W. Junk Publishers, Boston.

- Fox, M. W. 1971. Socio-ecological implications of individual differences in wolf litters: a developmental and evolutionary perspective. Behaviour, 41:298-313.

- Fox, M. 1972. Behaviour of Wolves, Dogs, and Related Canids. Harper and Row.

- Lockwood, R. 1979. Dominance in wolves–useful construct or bad habit. In Symposium on the Behavior and Ecology of Wolves. Edited by E. Klinghammer.

- Lopez, Barry H. (1978). Of Wolves and Men. J. M. Dent and Sons Limited.

- Mech, L. D. 1970. The wolf: the ecology and behavior of an endangered species. Doubleday Publishing Co., New York.

- Mech, L. David (1981). The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species. University of Minnesota Press.

- Mech, L. D. 1988. The arctic wolf: living with the pack. Voyageur Press, Stillwater, Minn.

- Mech, L. D., Adams, L. G., Meier, T. J., Burch, J. W., and Dale, B. W. 1998. The wolves of Denali. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- Mech, L. David. 2000. Alpha status, dominance, and division of labor in wolf packs. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center,

- Mech. L. D. and Boitani, L. 2003. Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. University of Chicago Press.

- Packard, J. M., Mech, L. D., and Ream, R. R. 1992. Weaning in an arctic wolf pack: behavioral mechanisms. Can. J. Zool. 70:1269-1275.

- O’Heare, J. 2003. Dominance Theory and Dogs. DogPsych Publishing.

- Rothman, R. J., and Mech, L. D. 1979. Scent-marking in lone wolves and newly formed pairs. Anim. Behav. 27:750-760.

- Schenkel, R. 1947. Expression studies of wolves. Behaviour, 1:81-129.

- Scott, J. P. and Fuller, J. L. 1998. Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog. University of Chicago Press.

- Van Hooff, J.A.R.A.M., and Wensing, J.A.B. 1987. Dominance and its behavioral measures in a captive wolf pack. In Man and wolf: advances, issues, and problems in captive wolf research. Edited by H. Frank. Dr. W. Junk Publishers, Boston.

- Wilson, E. O. 1975. Sociobiology. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

- Zimen, E. 1975. Social dynamics of the wolf pack. In The wild canids: their systematics, behavioral ecology and evolution. Edited by M. W. Fox. Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., New York. pp. 336-368.

- Zimen, E. 1976. On the regulation of pack size in wolves. Z. Tierpsychol. 40:300-341.

- Zimen, Erik (1981). The Wolf: His Place in the Natural World. Souvenir Press.

- Zimen, E. 1982. A wolf pack sociogram. In Wolves of the world. Edited by F. H. Harrington, and P. C. Paquet. Noyes Publishers, Park Ridge, NJ.

Gracias a Simon Gadbois (merci), Tilde Detz (tak), Victor Ros (gracias), Sue McCabe (go raibh math agate) y Parichart Abrantes (ขอบคุณครับ) por sus sugerencias para mejorar este artículo. Los fallos que puedan quedar son cosa mía, no suya.

Impreso en castellano la primera vez en Border Collie Magazine.