“Whether you (or I) follow a particular line of morality is not a necessary consequence of any model of social behavior. Moral stances are solely your (or my) decision” (Picture by Lisa J. Bains).

The dog trainers’ dispute about training methods blazes on unabated, with the erroneous and emotive use of terms such as dominance, punishment and leadership only adding fuel to the fire. There is no rational argumentation between the two main factions, one of which advocates a “naturalistic” approach and the other a “moralistic” stance. The term ‘dominance’ generates particular controversy and is often misinterpreted. We can detect, in the line of arguing about this topic, the same fundamental mistakes committed in many other discussions. By taking the controversy over dominant behavior as my example, I shall attempt to put an end to the feud by proving that neither side is right and by presenting a solution to the problem. Plus ratio quam vis—let reason prevail over force!

I shall demonstrate that the dispute is caused by:

(1) Blurring the boundaries between science and ethics. While ethics and morality deal with normative statements, science deals with factual, descriptive statements. Scientific statements are not morally right or wrong, good or bad.

(2) Unclear definitions. We cannot have a rational discussion without clear definitions of the terms used. Both sides in the dispute use unclear, incomplete definitions or none at all.

(3) Logical fallacies. The opposing sides commit either the ‘naturalistic fallacy,’ ‘the moralistic fallacy,’ or both. We cannot glean normative statements from descriptive premises, nor can we deduce facts from norms. The fact that something is does not imply that it ought to be; conversely, just because something ought to be does not mean that it is.

(4) Social conditioning and emotional load. As a result of inevitable social conditioning and emotional load, some terms develop connotations that can affect whether we like or dislike, accept or reject them, independent of their true meaning.

(5) Unclear grammar. The term dominance (an abstract noun) leads us to believe it is a characteristic of certain individuals, not an attribute of behavior. The correct use of the term in the behavioral sciences is as an adjective to describe a behavior, hence dominant behavior.

Bottom line: We need to define terms clearly and use them consistently; otherwise rational discussion is not possible. We must separate descriptive and normative statements, as we cannot derive what is from what ought to be or vice versa. Therefore, we cannot use the scientific concept of dominant behavior (or any descriptive statement) to validate an ethical principle. Our morality, what we think is right or wrong, is a personal choice; what is, or is not, is independent of our beliefs and wishes (we don’t have a choice).

Solution to the problem: The present dispute focuses on whether we believe it is right or wrong to dominate others (as in, totally control, have mastery over, command). It is a discussion of how to achieve a particular goal, about means and ends. It is a moral dispute, not a scientific quest. If both sides have similar goals in training their dogs, one way of settling the dispute is to prove that one strategy is more efficient than the other. If they are equally efficient, the dispute concerns the acceptability of the means. However, if either side has different goals, it is impossible to compare strategies.

My own solution of the problem: I cannot argue with people who believe it is right to dominate others (including non-human animals) as, even though I can illustrate how dominating others does not lead to harmony, I can’t make anyone choose harmony or define it in a particular way. I cannot argue with people who think it acceptable to hurt others in order to achieve their goals because such means are inadmissible to me. I cannot argue with people who deny or affirm a particular matter of fact as a means of justifying their moral conduct, because my mind rejects invalid, unsound arguments. With time, the rational principles that govern my mind and the moral principles that regulate my conduct may prove to be the fittest. Meanwhile, as a result of genetic pre-programming, social conditioning and evolutionary biology, I do enjoy being kind to other animals, respecting them for what they are and interacting with them on equal terms; I don’t believe it is right to subjugate them to my will, to command them, to change them; and I don’t need a rational justification as to why that’s right for me*.

“I do enjoy being kind to other animals, respecting them for what they are and interacting with them on equal premises; I don’t find it right to subjugate them to my will and dispositions, to command them, to change them; and I don’t need a rational justification for why that’s right for me” (Picture by Lisa J. Bain).

Argument

1 Science and ethics are not the same

Science is a collection of coherent, useful and probable predictions. All science is reductionist and visionary in a sense, but that does not mean that all reductionism is equally useful or that all visions are equally valuable or that one far-out idea is as acceptable as any other. Greedy reductionism is bound to fail because it attempts to explain too much with too little, classifying processes too crudely, overlooking relevant detail and missing pertinent evidence. Science sets up rational, reasonable, credible, useful and usable explanations based on empirical evidence, which is not connected per se. Any connections are made via our scientific models, ultimately allowing us to make reliable and educated predictions. A scientist needs to have an imaginative mind in order to think the unthinkable, discover the unknown and formulate initially far-fetched but verifiable hypotheses that may provide new and unique insights; as Kierkegaard writes, “This, then, is the ultimate paradox of thought: to want to discover something that thought itself cannot think.”

There are five legitimate criteria when evaluating a scientific theory or model: (1) evidence, (2) logic, (3) compatibility, (4) progression, and (5) flexibility.

(1) Evidence: a scientific theory or model must be based on credible and objective evidence. If there is credible evidence against it, we dismiss it. It must be testable and falsifiable.

(2) Logic: If a theory or model is based on logically invalid arguments or its conclusion are logically unsound, e.g. drawing valid conclusions from false premises, we must also dismiss it.

(3) Compatibility: If a theory or model shows crucial incompatibility with the whole body of science, then it is probably incorrect. If it is incompatible with another model, then we have a paradox. Paradoxes are not to be discarded, instead worked on and solved (or not solved as the case may be). Since “Paradoxes do not exist in reality, only in our current models of reality, […] they point the way to flaws in our current models. They therefore also point the way to further research to improve those models, fix errors, or fill in missing pieces.” In short, “scientists love paradoxes,” in the words of Novella.

(4) Progression: A scientific theory or model must explain everything that has already been explained by earlier theories, whilst adding new information, or explaining it in simpler terms.

(5) Flexibility: A theory or model must be able to accept new data and be corrected. If it doesn’t, then it is a dogma, not a scientific theory. A dogma is a belief accepted by a group as incontrovertibly true.

Science provides facts and uncovers important relationships between these facts. Science does not tell us how we should behave or what we ought to do. Science is descriptive, not normative. In other words: we decide what is right or wrong, good or bad, not necessarily depending on what science tells us.

Morality and science are two separate disciplines. I may not like the conclusions and implications of some scientific studies, I may even find their application immoral; yet, my job as a scientist is to report my findings objectively. Reporting facts does not oblige me to adopt any particular moral stance. The way I feel about a fact is not constrained by what science tells me. I may be influenced by it but, ultimately, my moral decision is independent of scientific fact. Science tells me men and women are biologically different in some aspects, but it does not tell me whether or not they should be treated equally in the eyes of the law. Science tells me that evolution is based on the algorithm “the survival of the fittest,” not whether or not I should help those that find it difficult to fit into their environment. Science informs me of the pros and cons of eating animal products, but it does not tell me whether it is right or wrong to be a vegetarian.

Ethologists study behavior on a biological and evolutionary basis, define the terms they use, find causal relationships, construct models for the understanding of behavior and report their findings. Ethologists are not concerned with morality. They simply inform us that the function of x behavior is y. They don’t tell us that because animal x does y, then y is right or wrong, good or bad, or that we ought or ought not do y.

The model I present in “Dominance—Making Sense of the Nonsense” is a scientific model that complies with all five of the requirements listed above.

(1) It is based on overwhelming data, i.e. given my definition of ‘dominant behavior,’ one cannot argue that it does not exist.

(2) The conclusions are logically consistent with the premises.

(3) It is consistent with our body of knowledge, particularly in the fields of biology and evolutionary theory.

(4) It explains what has been explained before and in more carefully defined terms.

(5) It accepts new data, adjustments and corrections (the current version is an updated version of my original from 1986). The model tells us nothing about morality. No single passage suggests that we should classify any particular relationship with our dogs as morally right or wrong. You will have to decide that for yourself. As an ethologist, I’m not concerned with what ought to be, only with what is. Echoing Satoshi Kanazawa, if I conclude something that is not supported by evidence, I commit a logical fallacy, which I must correct, and that’s my problem, but if my conclusion offends your beliefs, then that’s your problem.

Therefore, whether you (or I) follow a particular line of morality is not a consequence of any model of social behavior. Moral stances are solely your (or my) decision. It is not correct to draw normative judgments from descriptive claims. If you do so, you either commit the ‘naturalistic fallacy,’ the ‘moralistic fallacy’ or both, as I shall explain below (see point 3).

2 Unclear definitions

Having just pointed out the rigors of science, I must concede that the scientific community does bear some responsibility for the present dispute in as much as definitions and use of terms have sometimes been sloppy. Some researchers use particular terms (in this case ‘dominance’) without defining them properly and with slightly different implications from paper to paper.

Wikipedia writes: “Dominance (ethology) can be defined as an ‘individual’s preferential access to resources over another’ (Bland 2002). Dominance in the context of biology and anthropology is the state of having high social status relative to one or more other individuals, who react submissively to dominant individuals. This enables the dominant individual to obtain access to resources such as food or access to potential mates, at the expense of the submissive individual, without active aggression. The opposite of dominance is submissiveness. […] In animal societies, dominance is typically variable across time, […] across space […] or across resources. Even with these factors held constant, perfect dominant hierarchies are rarely found in groups of any size” (Rowell 1974 and Lorenz 1963).

It explains a dominance hierarchy as follows: “Individuals with greater hierarchical status tend to displace those ranked lower from access to space, to food and to mating opportunities. […] These hierarchies are not fixed and depend on any number of changing factors, among them are age, gender, body size, intelligence, and aggressiveness.”

Firstly, defining ‘dominance’ instead of ‘dominant behavior’ seems somewhat imprudent for a science that is intrinsically based on observational facts. It suggests we are dealing with an abstract quality when in fact we are referring to observable behavior (see point 5 below). Secondly, it implicitly equates ‘dominance’ with hierarchy (social status), which is misleading because some hierarchies may be supported by conditions other than dominant behavior. The use of the term ‘dominance hierarchy’ creates a false belief. Clearly, the terms dominance and dominant behavior are attributed with varying meanings, a highly unadvisable practice, particularly in stringently scientific matters.

As John Locke wrote in 1690 (An Essay Concerning Human Understanding), “The multiplication and obstinacy of disputes, which have so laid waste the intellectual world, is owing to nothing more than to this ill use of words. For though it be generally believed that there is great diversity of opinions in the volumes and variety of controversies the world is distracted with; yet the most I can find that the contending learned men of different parties do, in their arguings one with another, is, that they speak different languages. ”This has contributed […] to perplex the signification of words, more than to discover the knowledge and truth of things.”

To remedy this, I propose in “Dominance—Making Sense of the Nonsense” a set of carefully constructed definitions that are compatible with behavioral science and evolutionary theory, whilst paying special attention to the logical validity and consistency of the arguments. I’m convinced that we would avoid many pointless disputes if all those dealing with the behavioral sciences were to adopt such definitions.

Roughly speaking, there are currently two main schools of thought in dog training. For our present purpose, we shall call them ‘Naturalistic Dog Training’ and ‘Moralistic Dog Training.’ Of course, there are various other stances in between these two extremes, including a significantly large group of bewildered dog owners who do not adhere to any particular ideology, not knowing which way to turn.

Naturalistic Dog Training (aka the old school) claims their training echoes the dog’s natural behavior. They don’t provide a proper definition of dominance, but use it with connotations of ‘leader,’ ‘boss,’ ‘rank,’ implying that dominance is a characteristic of an individual, not of a behavior. In their eyes, some dogs are born dominant, others submissive, but all dogs need to be dominated because their very nature is to dominate or be dominated. They use this belief to justify their training methods that often involve punishment, flooding, coercion, and even shock collars, if deemed necessary, by the more extreme factions. For them, a social hierarchy is based on (assertive) dominance and (calm) submission, the leader being the most dominant. Their willingness to accept the existence of dominant behavior is motivated by their desire to validate their training theories, but their interpretation of the term is far from what ethologists understand by it.

Moralistic Dog Training (aka positive reinforcement training) distances itself from punishment, dominance, and leadership. They don’t define ‘dominance’ properly either, but use it with connotations of ‘punishment,’ ‘aggression,’ ‘coercion,’ ‘imposition.’ They claim dominance does not exist and regard it as a mere construct of philosophers and ethologists aimed at justifying the human tendency to dominate others. Their view is that we should nurture our dogs as if they were part of our family and should not dominate them. Therefore, they also distance themselves from using and condoning the use of terms like ‘alpha,’ ‘leader’ and ‘pack.’ The more extreme factions claim to refrain from using any aversive or signal that might be slightly connected with an aversive (like the word ‘no’) and deny their using of punishers (which, given the consensually accepted scientific definition of punishment, is a logical impossibility). Their refusal to accept the existence of dominant behavior is motivated by their desire to validate their training morality, but their interpretation of the term is again far from what ethologists understand by it.

An ethological definition of ‘dominant behavior’ is (as I suggest in “Dominance—Making Sense of the Nonsense”): “Dominant behavior is a quantitative and quantifiable behavior displayed by an individual with the function of gaining or maintaining temporary access to a particular resource on a particular occasion, versus a particular opponent, without either party incurring injury. If any of the parties incur injury, then the behavior is aggressive and not dominant. Its quantitative characteristics range from slightly self-confident to overtly assertive.”

This is a descriptive statement, a classification of a class of behaviors, so we can distinguish it from other classes of behaviors, based on the observable function of behavior (according to evolutionary theory). It is clearly distinguishable from the statements of both opposing mainstream dog-training groups in that it does not include any normative guidance.

3 Logical fallacies

A logical fallacy is unsound reasoning with untrue premises or an illogical conclusion. Logical fallacies are inherent in the logic structure or argumentation strategy and suit irrational desires rather than actual matters of fact.

An argument can be valid or invalid; and valid arguments can be sound or unsound. A deductive argument is valid if, and only if, the conclusion is entailed by the premises (it is a logical consequence of the premises). An argument is sound if, and only if, (1) the argument is valid and (2) all of its premises are true. The pure hypothetical syllogism is only valid if it has the following forms:

If P ⇒ Q and Q ⇒ R, then P ⇒ R

If P ⇒ ~R and ~R ⇒ ~Q, then P ⇒ ~Q

This mixed hypothetical syllogism has two valid forms, affirming the antecedent or “modus ponens” and denying the consequent or “modus tollens”:

If P ⇒ Q and P, then Q (modus ponens)

If P ⇒ Q and ~Q, then ~P (modus tollens)

It has two invalid forms (affirming the consequent and denying the antecedent).

The naturalistic fallacy is the mistake of identifying what is good with a natural property. In this fallacy, something considered natural is usually considered to be good, and something considered unnatural is regarded as bad. The structure of the argument is “P is natural, therefore P is moral” or “P is natural and non-P is unnatural, natural things are moral and unnatural things immoral, therefore P is moral and non-P immoral.” G. E. Moore coined the term naturalistic fallacy in 1903 in “Principia Ethica.” It is related to the ‘is-ought problem,’ also called ‘Hume’s Law’ or ‘Hume’s Guillotine,’ described for the first time by David Hume in 1739 in “A Treatise of Human Nature.” The ‘is-ought fallacy’ consists of deriving an ought conclusion from an is premise. The structure of the argument is “P is, what is ought to be, therefore P ought to be.”

The moralistic fallacy is the reverse of the naturalistic fallacy. It presumes that what ought to be preferable is what is, or what naturally occurs. In other words: what things should be is the way they are. E. C. Moore used the term for the first time in 1957 in “The Moralistic Fallacy.” The structure of the argument is, “P ought to be, therefore P is.”

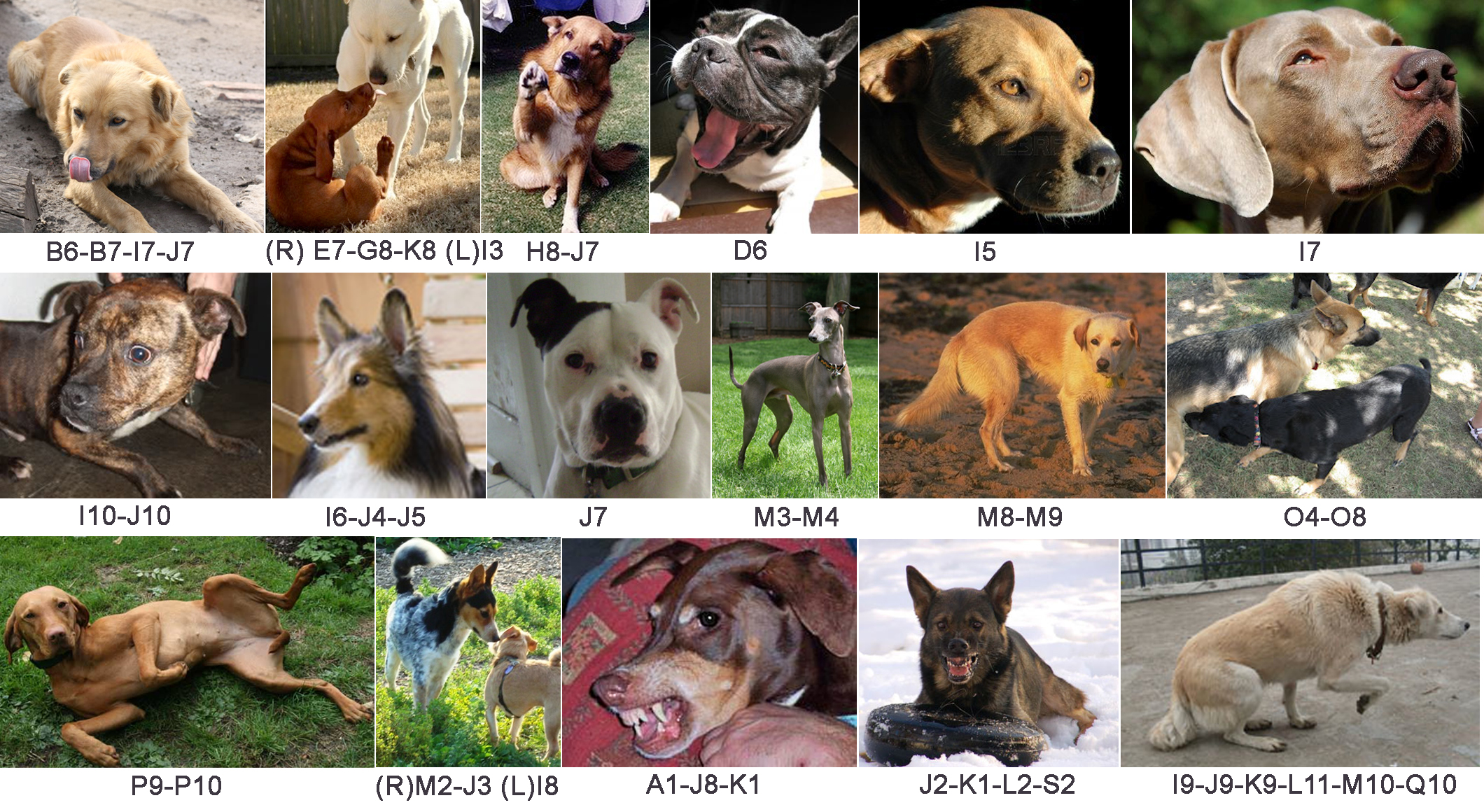

“There is no evidence that dogs attempt to dominate others or that they don’t. On the contrary, all evidence suggests that dogs (as most animals) use different strategies depending on conditions including costs and benefits. Sometimes they display dominant behavior, other times they display submissive behavior, and yet other times they display some other behavior” Picture by (L’Art Au Poil École).

The line of argumentation of Naturalistic Dog Training is: Dogs naturally attempt to dominate others; therefore, we ought to dominate them. We can transcribe this argument in two ways (argument 1a and 1b):

Argument 1a

(A) If the nature of dogs is to attempt to dominate others, then I ought to train dogs according to their nature. (P⇒Q)

(B) It is the nature of dogs to attempt to dominate others. (P)

Therefore: I ought to train dogs by attempting to dominate them. (Q)

Argument 1b

(A) If dogs dominate others, then it’s right to dominate others. (P⇒Q)

(B) If it’s right to dominate others, then I have to do the same to be right. (Q⇒R)

Therefore: If dogs dominate others, then I have to do the same to be right. (P⇒R)

We cannot derive ‘ought’ from ‘is.’ Arguments 1a and 1b commit the ‘naturalistic fallacy.’ Both arguments seem formally valid, except that they derive a norm from a fact. There is no logical contradiction in stating, “I ought not to train dogs according to their nature.” They are also unsound (the conclusions are not correct) because premises P are not true.

There is no evidence that dogs attempt to dominate others or that they don’t. On the contrary, all evidence suggests that dogs (like most animals) use different strategies depending on conditions, which include costs and benefits. Sometimes they display dominant behavior, other times they display submissive behavior, and other times they display other behavior. Even when particular dogs are more prone to use one strategy rather than another, we are not entitled to conclude that this is the nature of dogs.

Conclusion: whether science proves that dogs display or don’t display dominant behavior has nothing to do with whether or not it is morally right for us to dominate our dogs.

The line of argumentation of Moralistic Dog Training is: We ought not to attempt to dominate our dogs; therefore, dogs do not attempt to dominate us. We can transcribe this argument in two ways (argument 2a and 2b):

Argument 2a

(A) Dominance is bad. (P⇒Q)

(B) Dogs are not bad. (R⇒~Q)

Therefore: Dogs do not dominate. (R⇒~P)

Argument 2b

(A) If [dominance exists], it is . (P⇒Q)

(B) If it is , [dogs don’t do it]. (Q⇒R)

Therefore: if [dominance exists], [dogs don’t do it]. (P⇒R)

We cannot derive ‘is’ from ‘ought.’ Arguments 2a and 2b commit the ‘moralistic fallacy.’ Argument 2a is formally invalid even if the premises were true because the conclusion is not entailed in the premises (it is the same as saying red is a color, blood is not a color, so blood is not red). Argument 2b sounds a bit odd (in this form), but it is the only way I have found of formulating a valid argument from the moralistic trainers’ argument. It is formally valid but it is unsound because it commits the moralistic fallacy: in its second line, it derives a fact from a norm. It assumes that nature doesn’t do wrong (or what is good is natural), but there is no contradiction in assuming the opposite.

Conclusion: the fact we believe it is morally wrong to dominate our dogs does not mean that dogs do not display dominant behavior. We are entitled to hold such a view, but it does not change the fact that dogs display dominant behavior.

4 Social conditioning and emotional load

The choice of word by ethologists to coin the behavior in English, i.e. ‘dominant,’ also contributes to the dispute. Curiously enough, the problem does not exist in German where dominant and submissive behaviors are ‘überlegenes verhalten’ and ‘unterlegenes verhalten.’

All words we use have connotations due to accidental social conditioning and emotional load. A scientist knows he** cannot afford his judgment to be clouded by his own accidental social conditioning or emotions. A defined term means that and only that. It’s not good, not bad, not right, not wrong, and the issue of whether he likes it or not does not even enter the equation. As an individual he may have his own personal opinion and moral viewpoint, but he does not allow them to affect his scientific work. As individuals, we all have our own likes and dislikes because we are constantly being conditioned by our environment. Culture, trends, movements, environments, relationships and moods, all bias our attitudes towards particular terms. Nowadays, for reasons I will leave to historians and sociologists to analyze, the words ‘dominance’ and ‘submission’ have negative connotations for many people. When people, all of whom are subject to social conditioning, fail to distinguish between the scientific meaning of the words and their everyday connotations, they repudiate them, which is understandable.

Conclusion: a class of behavior that animals use to solve conflicts without harming one another is what ethologists call dominant and submissive behavior. This behavior, in the way I describe and define, exists (see above). You may not like the terms or indeed the behaviors, but that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. ‘Red’ is a characteristic of an object that provides particular information to our eyes as a result of the way it reflects or emits light. We can argue (and we do) about the definition of ‘red,’ what is red, what is not, when it becomes orange, but we do not deny that red exists. You may object to the name ‘red’ but objects will continue to reflect or emit light in a particular way that produces what we call red (or whatever we choose to call it). A ‘red flower’ (or a display of ‘dominant behavior’) is not an abstract concept, but a real, detectable thing, whilst the concept of ‘redness’ is an abstract notion, as are the concepts of ‘dominance,’ ‘height,’ ‘weight,’ ‘strength,’ etc…

5 Unclear grammar

Another problem is that we use the word dominance as a noun (an abstract noun in contrast to a concrete noun) when in this case it is (or should be) a ‘disguised adjective.’ Adjectives don’t make sense without nouns (except for adjectival nouns). Dominance is an abstract noun, something that by definition does not exist (otherwise it wouldn’t be abstract), except as an abstract notion of ‘showing dominant behavior’ and as in ‘dominant allele,’ ‘dominant trait,’ ‘dominant ideology,’ ‘dominant eye,’ etc. However, the behavior of alleles, traits, ideologies and eyes, which we call dominant or classify as dominant, exists. For example, the question “Do dogs show dominance towards humans?” uses the abstract noun ‘dominance’ as an adjectival noun instead of the more correct ‘dominant behavior’. This can be confusing for some as it suggests that dominance is an intrinsic quality of the individual, not the behavior. Therefore, I suggest that, in the behavioral sciences, we henceforth drop the adjectival noun and only use the term as an adjective to behavior. This is a very important point and a source of many misunderstandings and misconceptions regarding the character of behavior.

Behavior is dynamic and changeable. An individual displays one behavior at one given moment and another a while later. The popular view maintains the notion of a ‘dominant individual’ as the one that always shows dominant behavior and the ‘submissive individual’ as the one that always shows submissive behavior, which is not true. Dominant and submissive (dominance and submission) are characteristics of behavior, not individuals. Individuals may and do change strategies according to a particular set of conditions, although they may exhibit a preference for one strategy rather than another.

It is the ability to adopt the most beneficial strategy in the prevailing conditions that ultimately sorts the fittest from the less fit—moral strategies included.

Have a great day,

R—

______________

* This is my normative judgment and as such no one can contest it.

** The most correct form would be ‘he/she,’ or ‘he or she,’ but since I find it extremely ugly from a linguistic point of view (my normative judgment) to use this expression repeatedly, I chose to write, ‘he’ though not by any means neglecting the invaluable and indisputable contribution of my female colleagues.

- Canine Ethogram—Social and Agonistic Behavior (animals, behavior, dogs, evolution) 2012.06.29

- Pacifying Behavior—Origin, Function and Evolution (aggression, dogs, dominance, evolution, pacifying, submission) 2012.06.06

- Muzzle Grab Behavior in Canids (dogs, wolf, behavior) 2012.04.25

- Dominance—Making Sense of the Nonsense (aggression, fear, dominance, submission, biology, behavior, wolfs, dogs, genetics, hierarchy, social) 2011.12.11

- The Magic Words “Yes’ And ‘No’ (dogs, training, language, punishment, SMAF) 2011.11.27

- Signal and Cue—What is the Difference? (signal, cue, dog, training, behavior) 2011.10.07

- Commands or Signals, Corrections or Punishers, Praise or Reinforcers (behavior, dog, training) 2011.10.03

- Unveiling the Myth of Reinforcers and Punishers (behavior, behavior modification, reinforcers, punishers, operant conditioning) 2011.09.21

- The Spectrum of Behavior (behavior, aggression, fear, dominance, submission) 2011.09.09

- Magical Formula (behavior, evolution) 2011.09.04

References

- Abrantes, R. 1986. The Expression of Emotions in Man And Canid. Waltham Symposium, Cambridge, 14th-15th July 1986.

- Abrantes, R. 1997. The Evolution of Canine Social Behavior. Wakan-Tanka Publishers (2nd ed. 2005).

- Abrantes, R. 2011. Dominance—Making Sense Of The Nonsense.

- Ayer, A. J. 1972. Probability and Evidence. Macmillan, London.

- Bekoff, M. & Parker, J. 2010. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Univ. Of Chicago Press.

- Bland J. 2002 About Gender: Dominance and Male Behaviour.

- Copi, I. M. and Cohen, C. 1990. Introduction to Logic (8th ed.). Macmillan.

- Dennet, D. 1996. Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life. Simon & Schuster.

- Dennet, D. 2003. Freedom Evolves. Viking Press 2003.

- Futuyma, D. J. 1979. Evolutionary Biology. Sinauer Assoc.

- Galef, J. 2010. Hume’s Guillotine.

- Hewitt, S. E., Macdonald, D. W., & Dugdale, H. L. 2009. Context-dependent linear dominance hierarchies in social groups of European badgers, Meles meles. Animal Behaviour, 77, 161-169.

- Hume, D. 1739. A Treatise of Human Nature. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1967, edition.

- Locke, J. 1690. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

- Kanazawa, S. 2008. Two Logical Fallacies That We Must Avoid.

- Kierkegaard, S. 1844. Philosophiske Smuler eller En Smule Philosophi (Philosophical Fragments). Samlede Værker, Nordisk Forlag, 1936.

- Lorenz, K. 1963. Das sogenannte Böse. Zur Naturgeschichte der Aggression. Wien, Borotha-Schoeler Verlag, 1969.

- Moore, E. C. 1957. The Moralistic Fallacy. The Journal of Philosophy 54 (2).

- Moore, G. E. 1903. Principia Ethica.

- Novella, S. 2012. The Paradox Paradox.

- Pinker, S. How the Mind Works. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997.

- Popper, K. 1963. Conjectures and Refutations. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, UK.

- Popper, K. Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach. Oxford University Press.

- Rachels, J. 1990. Created From Animals. Oxford University Press.

- Rowell, T. E. 1974. The Concept of Social Dominance. Behavioral Biology, 11, 131-154.

- Ruse, M. 1986. Taking Darwin seriously: a naturalistic approach to philosophy. Prometheus Books.

Thanks to Anabela Pinto-Poulton (PhD, Biology), Simon Gadbois (PhD, Biology), Stéphane Frevent (PhD, Philosophy), Victor Ross (Graduate Animal Trainer EIC), Parichart Abrantes (MBA), and Anna Holloway (editor) for their suggestions to improve this article. The remaining flaws are mine, not theirs.