—A Comparative Analysis of Dogs and Horses

Abstract

Bonding is a central feature of social life in many animal species, yet the terms bonding, attachment, and imprinting are often conflated in both scientific and popular discourse. This article examines bonding as a biological and behavioral process, distinguishing its proximate mechanisms from its ultimate evolutionary functions. Focusing on two companion species with contrasting evolutionary ecologies—domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) and domestic horses (Equus ferus caballus)—we compare how imprinting, attachment, and broader bonding processes emerge across development and social contexts. Drawing on ethology, comparative studies, and neurobiological research, we show that while early attachment relationships are developmentally constrained and species-specific, enduring social bonds are more flexibly shaped by shared experience, social regulation, and cooperative activity. We further argue that bonding should be understood not merely as an affiliative state, but as a regulatory process that supports coordination, stress regulation, and cooperation. By integrating evolutionary, developmental, and mechanistic perspectives, this comparative analysis clarifies key conceptual distinctions, common principles, and meaningful differences in social bonding across two different species.

Bonding—a Definition

In animal behavior, bonding refers to a biologically grounded process by which individuals—of the same or different species—develop stable, selective social relationships that are maintained over time. The primary adaptive functions of bonding include promoting coordination, cooperation, and mutual tolerance, thereby enhancing individual fitness and, in many cases, inclusive fitness.1 2

Bonding is expressed through recurrent interaction patterns that regulate access, proximity, and coordinated activity among partners. Its strength, duration, and symmetry vary widely across species and social contexts, ranging from transient affiliations to enduring, lifelong bonds.

Parent–Offspring Bonding and Attachment

The term attachment is used cautiously in ethology.3 When employed, it represents a functional and descriptive label for a particular regulatory organization of social behavior, rather than as a reference to inferred mental states or subjective experience. Ethological usage has historically emphasized parent–offspring relationships, especially during periods of functional dependency (Hinde, 1982; Bateson, 1994), and has cautioned against unqualified extension of the term to adult social relationships (Hinde, 1976; Silk, 2007).

In the present paper, we treat attachment as a specialized form of bonding, defined ethologically as a pattern of selective proximity regulation and context-dependent separation responses that serves regulatory and adaptive functions. While attachment is often most clearly expressed in filial contexts, it is not defined by age or developmental stage, but by its functional structure.

The most fundamental and extensively studied form of bonding occurs between parents and offspring. In this context, bonding frequently takes the form of attachment. Filial attachment promotes proximity maintenance, contributes to the regulation of distress during separation, and provides a secure base from which juveniles can explore their environment.

Filial attachment is typically most pronounced during periods of dependency and becomes less central as the juvenile attains functional independence. Nevertheless, early attachment-related interactions can exert enduring effects on later social behavior, stress responsiveness, and affiliative tendencies (Bowlby, 1982; Carter, 1998).4 5

In domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris), a well-documented sensitive period for social attachment occurs approximately between the third and tenth weeks of age. During this phase, puppies readily form selective social relationships with conspecifics and humans. Individuals deprived of typical social contact beyond roughly 14 weeks of age often show persistent alterations in social behavior, including reduced affiliative responsiveness and atypical interaction patterns relative to species- and population-specific norms (Scott & Fuller, 1965; Freedman et al., 1961).

Pair Bonding and Reproductive Cooperation

In many social species, males and females form pair bonds during courtship and mating. These bonds support coordinated reproductive behavior, including shared parental investment, mate guarding, or cooperative resource defense, thereby increasing the likelihood that shared genetic material is successfully transmitted to subsequent generations.

Pair bonding is functionally and evolutionarily favored in species where ecological conditions—e.g., prolonged offspring dependency, biparental care need, mate guarding, or dispersed resources—make sustained cooperation between reproductive partners more likely to increase the survival and reproductive success of their shared offspring, thereby enhancing the direct fitness of both parents (Clutton-Brock, 1991).

Pair bonds may incorporate attachment-like regulatory features, such as selective proximity and partner-specific buffering of stress. Yet, they are functionally distinct from filial attachment in that they primarily serve reproductive coordination rather than developmental dependency (Clutton-Brock, 1991).

Social Bonding Beyond Attachment

Among group-living animals, bonding also arises through repeated interaction, cohabitation, and shared ecological challenges. Such bonds need not involve attachment in the strict sense—that is, they may lack pronounced separation responses or stress-buffering functions—yet they remain stable and functionally significant.

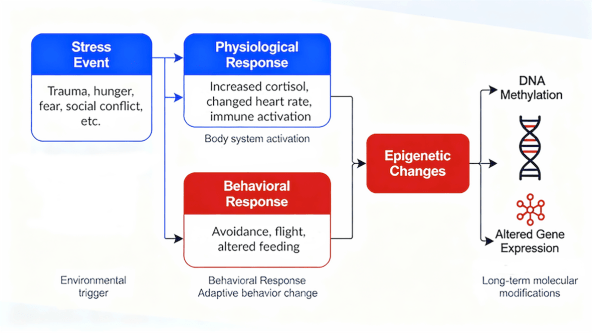

Behaviors such as grooming, play, coalitionary support, and reciprocal food sharing are widespread mechanisms for maintaining social bonds. Shared intense experiences (Fig. 2), including coordinated responses to threats, are particularly effective in strengthening affiliative ties among adults, as they reduce uncertainty regarding partners’ reliability in critical contexts (Silk, 2007).6

Bonding should therefore not be understood solely as an affiliative or affective state, but also as a regulatory process emerging from shared coping with challenge and uncertainty, in which moderate, manageable stress can facilitate learning, coordination, and social cohesion (Carter, 1998; Insel & Young, 2001; Abrantes, 2025).

Figure 2. Cooperative interaction among members of Micromys minutus (photo by Cuttestpaw).

Shared, demanding interactions can contribute to the formation and reinforcement of social bonds. Bonding, attachment, and imprinting represent distinct biological processes with different developmental timing and functions (see Table 1).

Neurobiological Substrates of Bonding and Attachment

At a proximate level, affiliative interactions are associated with neuroendocrine processes, notably the release of oxytocin, which modulates defensive responses and facilitates social approach, tolerance, and coordination (Carter, 1998; Insel & Young, 2001). These mechanisms support both broad social bonding and the more specific dynamics of attachment.

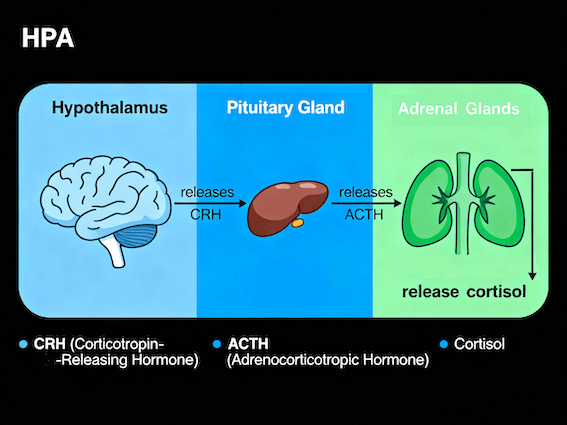

Attachment, however, also recruits systems involved in stress regulation and separation responses, including the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, endogenous opioid systems, and associated neural circuits that mediate distress and recovery during separation and reunion. These systems support the regulatory functions of attachment by modulating arousal, persistence, and recovery in the absence of social contact, distinguishing attachment from broader forms of social bonding (Carter, 1998; Insel & Young, 2001).

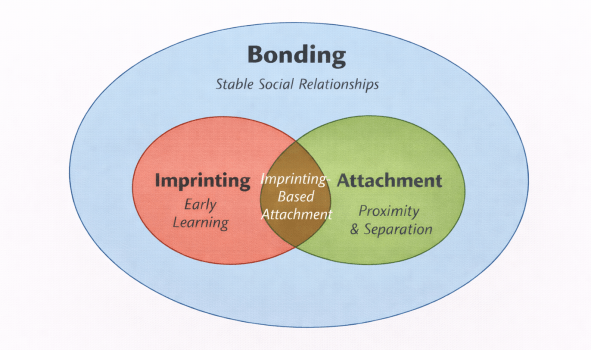

Bonding represents the broad class of enduring affiliative social relationships that support cooperation, tolerance, and social regulation. Attachment constitutes a functionally specialized subset of bonding, characterized by selective proximity seeking and separation-related regulatory processes, most commonly expressed during periods of dependency but not restricted to them. Imprinting is a phase-sensitive learning process that can establish stable social preferences and thereby contribute to bond formation. The overlap between imprinting and attachment (imprinting-based attachment) reflects cases in which early learning supports the emergence of attachment relationships. The diagram emphasizes that bonding encompasses a broader range of social relationships than either imprinting or attachment alone, and that neither imprinting nor attachment is necessary for bonding to occur.

Bonding, Attachment, and Imprinting

Bonding is often discussed alongside imprinting, but the concepts are not interchangeable. While imprinting produces a bond, not all bonding involves imprinting, and not all bonds involve attachment7 (see Table 1).

Imprinting refers to a form of phase-sensitive learning that occurs during a restricted developmental window, is rapid, and appears largely independent of the immediate consequences of behavior. Some species are predisposed to acquire specific information—such as caregiver identity or species recognition—during these sensitive periods. This learning reflects evolved developmental programs rather than associative conditioning (Lorenz, 1935; Bateson, 1979).8

Attachment, by contrast, develops through ongoing interaction and experience. Although it often emerges during sensitive periods, it remains modifiable and is regulated by feedback from the caregiver–offspring relationship.

At the level of bonding as a general social process, fitness benefits may accrue through both direct and inclusive pathways, depending on whether bonds involve reproductive partners, kin, or non-kin; by contrast, pair bonding specifically enhances direct fitness via increased offspring survival.

Table 1—Terminological Comparison: Bonding, Attachment, and Imprinting

| Term | Core Definition | Developmental Timing | Learning Mechanism | Typical Duration | Functional Role | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonding | A biologically grounded process through which individuals form stable, selective social relationships maintained over time | Any life stage | Multiple mechanisms: associative learning, repeated interaction, shared experience; neuroendocrine facilitation (e.g., oxytocin) | Variable; from transient to lifelong | Promotes coordination, cooperation, tolerance, and social stability; enhances individual and inclusive fitness | Carter, 1998; Insel & Young, 2001; Silk, 2007 |

| Attachment | A functionally specialized form of bonding characterized by selective proximity regulation and context-dependent separation responses | Not developmentally restricted; often most pronounced during periods of dependency | Experience-dependent learning supporting proximity regulation, stress modulation, and partner-specific responses | Typically long-lasting; expression may change across contexts and life stages | Regulates proximity, buffers stress, and supports adaptive performance under vulnerability | Bowlby, 1969/1982; Carter, 1998; Insel & Young, 2001 |

| Imprinting | A developmentally constrained learning process through which specific stimuli or social partners acquire enduring salience | Restricted sensitive or critical period | Rapid, often non-associative or weakly associative learning; relatively resistant to extinction | Typically long-lasting or irreversible | Biases later recognition, preference, or social orientation; may shape but does not constitute bonding or attachment | Lorenz, 1935; Bateson, 1979; Horn, 2004 |

Bonding and Attachment in Domestic Dogs

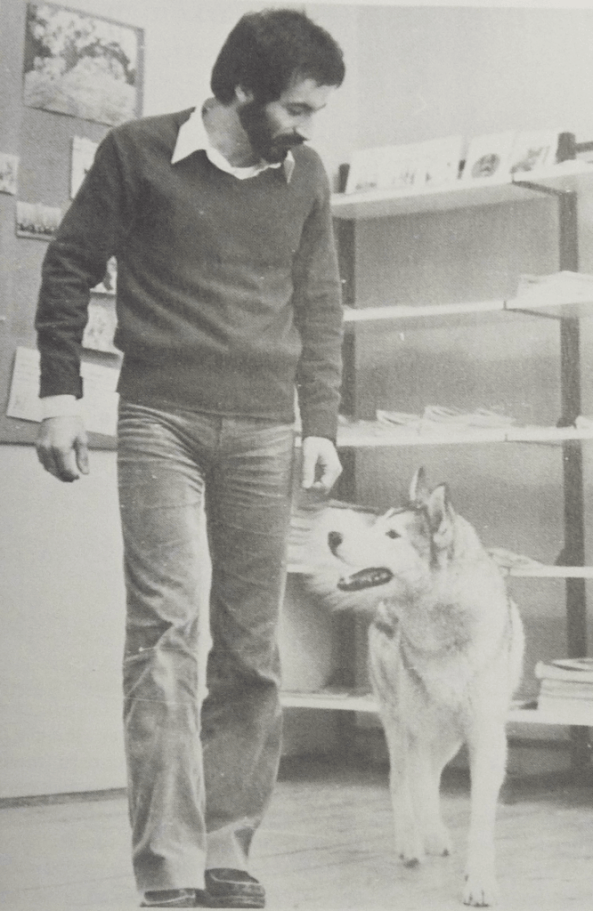

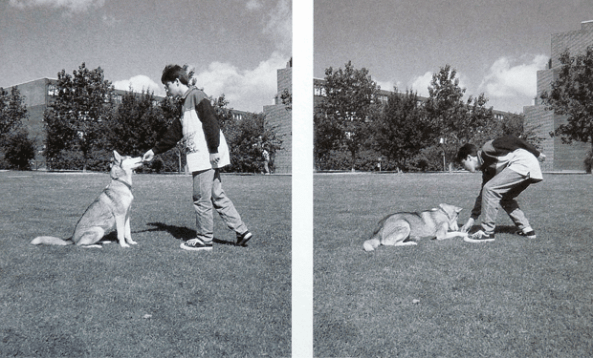

In domestic environments, dogs develop social bonds and, in many cases, attachment relationships through everyday interaction. Grooming, resting in proximity, play, coordinated vocal responses, and joint reactions to environmental disturbances contribute to the formation and maintenance of affiliative bonds.

Dogs form attachment relationships not only with conspecifics but also with humans, as evidenced by selective proximity regulation, stress modulation, and differential behavioral responses to familiar versus unfamiliar individuals (Topál et al., 1998; Gácsi et al., 2013). They may also form stable bonds with individuals of other species, such as household cats, reflecting the flexibility of canine social bonding systems.

Beyond early attachment formation, domestic dogs establish stable, selective social bonds with both conspecifics and humans. Preferred social partners, asymmetries in play solicitation, and selective proximity patterns cannot be explained by familiarity alone (Bradshaw & Nott, 1995; Cafazzo et al., 2010). These bonds are associated with measurable stress-buffering effects: the presence of a familiar human or canine partner reduces behavioral indicators of distress and attenuates physiological stress responses in challenging situations (Gácsi et al., 2013; Nagasawa et al., 2015).

Bond strength is not maintained by passive affiliation alone. Coordinated activity under mild challenge, including problem-solving and shared task engagement, appears particularly effective in reinforcing dog–human bonds, consistent with the view that shared regulation under manageable stress promotes durable social bonding (Gácsi et al., 2013; Nagasawa et al., 2015; Abrantes, 2025).

At a proximate level, affiliative interactions between dogs and humans—including mutual gaze, physical contact, and coordinated activity—are associated with increased oxytocin in both partners, supporting a conserved neuroendocrine substrate for social bonding across species (Odendaal & Meintjes, 2003; Nagasawa et al., 2015). While dogs readily form attachment relationships with humans, these attachments remain experience-dependent, shaped by consistency, predictability, and shared activity rather than by imprinting alone, reinforcing the distinction between early phase-sensitive learning and later-developing attachment bonds.

Bonding and Attachment in Domestic Horses

Domestic horses (Equus ferus caballus) are highly social, herd-living mammals in which bonding plays a central role in survival and welfare. In both free-ranging and managed populations, horses form stable affiliative relationships, expressed through preferred spatial proximity, synchronized activity, and allogrooming—a behavior closely associated with social tolerance and group cohesion (Waring, 2003; Budiansky, 1997). These bonds support collective vigilance and coordinated responses to potential threats, consistent with the horse’s evolutionary history as a socially obligate prey species.

The most prominent attachment relationship in horses is the mare–foal bond, which develops rapidly after birth and is essential for protection, learning, and early social development. Foals show selective following and behavioral disruption upon separation, while mares provide regulation through proximity and intervention. This attachment is strongest during early dependency and gradually diminishes as juveniles integrate into the wider social group. Evidence indicates that early social deprivation or premature separation can produce long-term effects on social behavior and responses to novelty and handling, highlighting the developmental importance of early attachment in horses (Søndergaard & Jago, 2010).

Beyond early development, adult horses form selective social bonds within the herd. Although these relationships do not necessarily meet strict attachment criteria—such as selective proximity regulation under acute stress—they are persistent and functionally significant. Preferred partners are associated with reduced behavioral indicators of fear and improved coping in challenging situations, suggesting that adult social bonding in horses serves a regulatory and stress-buffering function (Christensen et al., 2008; Lansade et al., 2008). Horses may also form bonds with humans; however, these relationships are best understood as experience-dependent and context-specific, shaped by predictability and shared activity rather than by imprinting or caregiver-style attachment (Waring, 2003; Budiansky, 1997).

In horses, as in dogs, bonding is more reliably reinforced through shared activity and coordinated responses to environmental challenges than through passive contact alone, consistent with a regulatory—rather than purely affiliative—interpretation of social bonding (Christensen et al., 2008; Lansade et al., 2008; Abrantes, 2025).

Comparative Perspective: Dogs and Horses

Dogs and horses illustrate how bonding and attachment processes are shaped by species-specific ecology while relying on shared biological principles (see Table 2). Dogs, as socially flexible carnivores shaped by intensive human-directed selection, readily form attachment relationships with humans that functionally resemble caregiver–offspring systems in key regulatory respects. Horses, as socially obligate prey animals, emphasize herd cohesion, mutual tolerance, and collective regulation, with attachment largely confined to early development and selected interspecific contexts.

In both species, enduring bonds are more reliably strengthened through shared experience and coordinated activity than through passive contact alone. These contrasts underscore the importance of distinguishing ultimate evolutionary function from proximate mechanisms, while demonstrating that bonding remains a general, cross-species process grounded in cooperation, regulation, and survival.

Table 2—Imprinting, Attachment, and Bonding in Domestic Dogs and Horses

| Dimension | Dogs (Canis familiaris) | Horses (Equus ferus caballus) |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary niche | Social carnivore (predator) (Clutton-Brock, 1991) | Social herbivore (prey) (Waring, 2003) |

| Primary social ecology | Flexible social grouping; high social plasticity (Bradshaw & Nott, 1995) | Stable herd structure; social conservatism (Budiansky, 1997; Waring, 2003) |

| Imprinting | Clear sensitive period for social orientation (≈3–10 weeks), extendable to humans (Scott & Fuller, 1965; Freedman et al., 1961) | Primarily mare–foal recognition; limited beyond neonatal period (Waring, 2003) |

| Function of imprinting | Establishes early social orientation toward conspecifics and humans (Scott & Fuller, 1965) | Ensures early maternal recognition and cohesion (Waring, 2003) |

| Attachment (juvenile) | Strong puppy–caregiver attachment; selective proximity regulation and distress modulation (Topál et al., 1998) | Strong mare–foal attachment; declines with social integration (Søndergaard & Jago, 2010) |

| Attachment (adult) | Common toward humans; selective proximity regulation and stress buffering toward familiar partners (Topál et al., 1998; Gácsi et al., 2013) | Rare and context-specific; not typically expressed as proximity regulation under stress (Waring, 2003; Budiansky, 1997) |

| Bonding (conspecifics) | Selective social bonds; play and tolerance asymmetries (Bradshaw & Nott, 1995; Cafazzo et al., 2010) | Selective affiliative bonds; proximity and allogrooming (Waring, 2003) |

| Bonding (interspecific) | Stable, enduring bonds with humans common (Topál et al., 1998) | Bonds with humans experience-dependent and task-related (Budiansky, 1997) |

| Stress modulation by social partners | Strong; familiar humans or dogs reduce behavioral and physiological stress (Gácsi et al., 2013; Odendaal & Meintjes, 2003) | Moderate; preferred partners reduce fear responses and improve coping (Christensen et al., 2008; Lansade et al., 2008) |

| Bonding and stress regulation | Shared exposure to manageable challenges strengthens bonds via mutual regulation (Gácsi et al., 2013; Abrantes, 2025) | Shared coping and coordinated activity strengthen bonds via stress buffering (Christensen et al., 2008; Abrantes, 2025) |

| Neuroendocrine correlates | Oxytocin associated with human–dog bonding and stress modulation (Odendaal & Meintjes, 2003; Nagasawa et al., 2015) | Less directly studied; stress modulation inferred behaviorally and physiologically (Lansade et al., 2008) |

| Role of shared activity | Central to bond strengthening (Bradshaw & Nott, 1995; Abrantes, 2025) | Central to bond strengthening (Budiansky, 1997; Abrantes, 2025) |

| Risk of anthropomorphic misinterpretation | High if attachment inferred beyond demonstrated regulatory criteria (Topál et al., 1998) | High if attachment inferred without evidence of proximity regulation under stress (Waring, 2003) |

Note. References listed in each cell are representative primary or synthetic sources supporting the stated patterns, not an exhaustive review. The table contrasts dominant tendencies shaped by species-specific ecology (predator vs. prey) and domestication history; individual variation and contextual effects are expected in both species.

Practical Implications for Human–Animal Interaction

The distinctions developed in this paper—between bonding, imprinting, and attachment—have direct implications for how humans interact with companion animals in everyday contexts. First, recognizing that imprinting is developmentally constrained, while attachment and bonding are not, underscores the importance of early social experience, particularly in dogs and in the mare–foal relationship in horses. In dogs, early social deprivation during sensitive periods has been shown to produce long-lasting deficits in social behavior and adaptability (Freedman et al., 1961; Scott & Fuller, 1965), while in horses, early handling and the quality of the mare–foal relationship significantly influence later responses to humans and novel situations (Søndergaard & Jago, 2010). These findings indicate that missed or impoverished early social exposure cannot be fully compensated for later by affiliative contact alone.

Second, understanding bonding as an experience-dependent and regulatory process shifts the emphasis from passive affiliative gestures to shared activity. While behaviors such as petting or eye contact can support short-term social engagement, empirical work in dogs shows that attachment-related stress buffering and proximity regulation are more robustly expressed in contexts involving coordinated interaction and human participation (Topál et al., 1998; Gácsi et al., 2013). Similarly, studies in horses indicate that social buffering effects are most evident when animals face challenges in the presence of a familiar partner, rather than through proximity alone (Christensen et al., 2008; Lansade et al., 2008).

Third, the role of manageable stress and challenge in bonding suggests that optimal interaction does not require eliminating all difficulty. Moderate stress, when predictably regulated and socially mediated, can facilitate learning and social cohesion rather than undermine it (Carter, 1998; Insel & Young, 2001). This interpretation is consistent with comparative evidence showing that shared coping with environmental or task-related challenges strengthens affiliative relationships in both dogs and horses (Gácsi et al., 2013; Christensen et al., 2008), and aligns with a regulatory rather than hedonic understanding of bonding (Abrantes, 2025).

Finally, distinguishing bonding from attachment helps prevent anthropomorphic expectations. Dogs readily form attachment relationships with human partners that meet established behavioral criteria, including selective proximity regulation and stress buffering (Topál et al., 1998; Gácsi et al., 2013), whereas horses typically do not exhibit attachment patterns that map onto caregiver–offspring models, despite forming stable and meaningful social bonds (Waring, 2003; Budiansky, 1997). Recognizing these species-specific differences allows humans to interact more effectively and more respectfully with each animal, aligning expectations with biological and ecological realities rather than with human social norms (Clutton-Brock, 1991).

Conclusion

This analysis has aimed to clarify the concept of bonding by situating it within a comparative and evolutionary framework, while carefully distinguishing it from attachment and imprinting. Using domestic dogs and horses as case studies, we have shown that bonding is neither reducible to early phase-sensitive learning nor synonymous with attachment relationships, even when these processes overlap in development and function (Bateson, 1979; Bowlby, 1982). Rather, bonding emerges as a flexible, experience-dependent process grounded in repeated interaction, shared activity, and social regulation (Carter, 1998; Insel & Young, 2001).

The comparison between dogs and horses illustrates how species-specific ecology and domestication history shape the expression of social relationships. Dogs, as socially plastic carnivores selected for close cooperation with humans, readily form attachment relationships with human partners that persist into adulthood and meet established regulatory criteria (Topál et al., 1998; Gácsi et al., 2013). Horses, by contrast, as socially obligate prey animals, emphasize herd cohesion and selective affiliative bonds, with attachment most clearly expressed in early developmental contexts and selected interspecific situations (Waring, 2003; Budiansky, 1997). Despite these differences, both species demonstrate that enduring bonds are strengthened more by coordinated action and shared coping with challenge than by passive affiliation (Christensen et al., 2008; Gácsi et al., 2013).

More broadly, distinguishing ultimate evolutionary explanations from proximate bonding mechanisms helps avoid both anthropomorphism and unwarranted generalization (Hamilton, 1964; Tinbergen, 1963). Bonding can be favored by natural selection in species where it promotes cooperation, tolerance, survival, and reproductive success. Yet, it is instantiated through learning, social experience, and physiological regulation rather than through intention or moral sentiment. Recognizing this multi-level structure allows for a more precise and biologically grounded understanding of social relationships in companion animals. It provides a model that can be extended—cautiously and explicitly—to other social species.

Footnotes

- Inclusive fitness refers to the total genetic contribution an individual makes to subsequent generations, including both direct reproduction and effects on the reproductive success of genetically related individuals, weighted by degree of relatedness. This concept explains how social behaviors that appear altruistic at the individual level can be favored by natural selection when they enhance the transmission of shared genes (Hamilton, 1964). ↩︎

- Inclusive fitness provides an ultimate, evolutionary explanation for why bonding can be favored by natural selection; the formation and maintenance of bonds themselves depend on proximate mechanisms, including development, learning, social experience, and neuroendocrine regulation. ↩︎

- Psychological frameworks of attachment, including the Strange Situation paradigm (Ainsworth et al., 1978) and its application to dogs by Topál et al. (1998), are cited here solely for their operational separation–reunion criteria. These approaches originate in human developmental psychology and have generated ongoing discussion regarding their scope and interpretation when applied across species or beyond early developmental contexts (Hinde, 1982; Wynne, 2004; Buller, 2005). In the present paper, their use is restricted to clearly defined behavioral patterns, without theoretical commitments concerning mental states or emotional experience. ↩︎

- Bowlby explicitly characterizes attachment in biological terms: “Attachment behaviour is regarded as a class of social behaviour of an importance equivalent to that of mating behaviour and parental behaviour. It is held to have a biological function specific to itself […]” (Bowlby, 1982, p. 223). This formulation treats attachment as an evolved behavioral system defined by function rather than by species-specific expression. ↩︎

- Carter summarizes the functional role of social attachment as follows: “[…] social attachments function to facilitate reproduction, provide a sense of security and reduce feelings of stress or anxiety” (Carter, 1998, p. 779). ↩︎

- As a general evolutionary principle, Silk defines the conditions under which sociality evolves as follows: “[…] sociality evolves when the net benefits of close association with conspecifics exceed the costs” (Silk, 2007, p. 539). This formulation provides the ultimate-level framework within which affiliative behaviors such as grooming, play, and cooperative defense can be understood as mechanisms that increase the reliability and benefits of social partners. ↩︎

- The statement that imprinting produces a bond refers to the fact that imprinting establishes a stable social preference or orientation toward a particular individual, class of individuals, or stimulus, thereby generating an affiliative relation. However, imprinting is only one possible developmental pathway to bonding. Many bonds—such as adult affiliative relationships, cooperative partnerships, or interspecific social bonds—arise through repeated interaction, shared experience, and social regulation outside any restricted sensitive period. Conversely, not all bonds involve attachment in the strict sense defined by selective proximity seeking and distress regulation under separation. Attachment represents a specific subset of bonds, typically associated with dependency and security regulation, whereas bonding is the broader category encompassing a range of affiliative and cooperative social relationships (Bowlby, 1982; Bateson, 1979; Carter, 1998). ↩︎

- The term imprinting (original German Prägung) was introduced by Konrad Lorenz to describe a distinctive form of early learning observed in birds, characterized by rapid acquisition, restricted to a sensitive developmental period, and relatively independent of reinforcement (Lorenz, 1935). Early formulations emphasized the apparent irreversibility of imprinting effects; however, subsequent research has shown that while imprinting outcomes are often highly stable, they are not invariably permanent and may be modifiable under certain conditions, particularly with later experience or altered social environments (Bateson, 1979; Horn, 2004). Significantly, this qualification does not undermine the core concept. Instead, it reflects a broader shift away from rigid dichotomies between innate and learned behavior toward a developmental perspective in which evolved predispositions interact with experience. Although the term imprinting has declined in frequency relative to broader constructs such as early learning or developmental plasticity, it remains scientifically relevant as a label for phase-sensitive learning processes that are rapid, time-constrained, and shaped by species-specific developmental programs rather than by associative conditioning alone. ↩︎

References

Abrantes, R. (2025, November 24). Stress helps learning and bonding.

https://rogerabrantes.com/2025/11/24/stress-helps-learning-and-bonding/

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 9780470267079

Bateson, P. (1979). How do sensitive periods arise and what are they for? Animal Behaviour, 27(2), 470–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-3472(79)90184-2

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd ed.). Basic Books. (Original work published 1969). ISBN 9780465005437

Bradshaw, J. W. S., & Nott, H. M. R. (1995). Social and communication behaviour of companion dogs. In J. Serpell (Ed.), The domestic dog: Its evolution, behaviour and interactions with people (pp. 115–130). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521415293

Budiansky, S. (1997). The nature of horses: Exploring equine evolution, intelligence, and behavior. Free Press. ISBN 9780684827681

Buller, D. J. (2005). Adapting minds: Evolutionary psychology and the persistent quest for human nature. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262524608

Cafazzo, S., Valsecchi, P., Bonanni, R., & Natoli, E. (2010). Dominance in relation to age, sex, and competitive contexts in a group of free-ranging domestic dogs. Behavioral Ecology, 21(3), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arq001

Carter, C. S. (1998). Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 23(8), 779–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(98)00055-9

Christensen, J. W., Malmkvist, J., Nielsen, B. L., & Keeling, L. J. (2008). Effects of a calm companion on fear reactions in naïve test horses. Equine Veterinary Journal, 40(1), 46–50. https://doi.org/10.2746/042516408X245171

Clutton-Brock, T. H. (1991). The evolution of parental care. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691024685

Freedman, D. G., King, J. A., & Elliot, O. (1961). Critical period in the social development of dogs. Science, 133(3457), 1016–1017. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.133.3457.1016

Gácsi, M., Maros, K., Sernkvist, S., Faragó, T., & Miklósi, Á. (2013). Human analogue safe haven effect of the owner: Behavioural and heart rate response to stressful social stimuli in dogs. PLoS ONE, 8(3), e58475. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058475

Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4

Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. II. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7(1), 17–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(64)90039-6

Horn, G. (2004). Pathways of the past: The imprint of memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5(2), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1324

Insel, T. R., & Young, L. J. (2001). The neurobiology of attachment. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2(2), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1038/35053579

Lansade, L., Bouissou, M.-F., & Erhard, H. W. (2008). Fearfulness in horses: A temperament trait stable across time and situations. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 109(2–4), 355–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2008.06.011

Lorenz, K. (1935). Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vogels. Journal für Ornithologie, 83, 137–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01905355

Nagasawa, M., Mitsui, S., En, S., et al. (2015). Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human–dog bonds. Science, 348(6232), 333–336. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261022

Odendaal, J. S. J., & Meintjes, R. A. (2003). Neurophysiological correlates of affiliative behaviour between humans and dogs. The Veterinary Journal, 165(3), 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-0233(02)00237-X

Scott, J. P., & Fuller, J. L. (1965). Genetics and the social behavior of the dog. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226743430

Silk, J. B. (2007). The adaptive value of sociality in mammalian groups. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 362(1480), 539–559. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2006.1994

Søndergaard, E., & Jago, J. G. (2010). The effect of early handling of foals on their reaction to handling, humans and novelty, and the foal–mare relationship. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 123(3–4), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2010.01.006

Tinbergen, N. (1963). On aims and methods of ethology. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 20(4), 410–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.1963.tb01161.x

Topál, J., Miklósi, Á., Csányi, V., & Dóka, A. (1998). Attachment behavior in dogs (Canis familiaris): A new application of Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Test. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 112(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7036.112.3.219

Waring, G. H. (2003). Horse behavior (2nd ed.). William Andrew Publishing. ISBN 9780815514871

Wynne, C. D. L. (2004). Do animals think? Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691118650

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.