When we ran our traditional on-campus programs at the Ethology Institute, the new students would invariably divide into two groups: those who wanted to become dog trainers and those who wanted to become horse trainers. Every year, I told them the same: “If you want to become good trainers of your favorite species, you must also train other species—you must gain perspective.”

In principle, it doesn’t matter which other animals you train. Cats, rats, parrots—each offers its own valuable lessons. However, there is one small and charming creature that stands out to me as the almost ideal teacher. It is social, curious, shy, and relatively easy to train. You have probably guessed it: the guinea pig (Cavia porcellus).

Today, I’m going to share how these little, cute animals can help you become a better dog trainer, a better horse trainer, a better animal trainer—and, most importantly, a more complete individual. Please, keep reading.

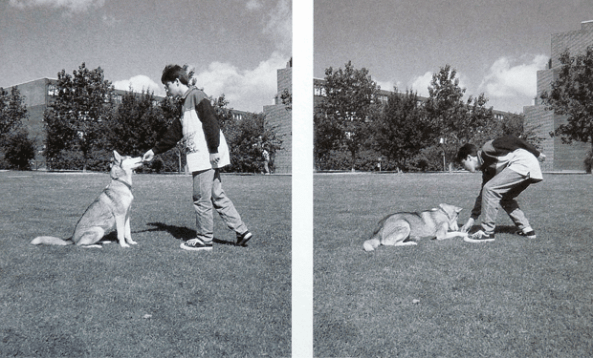

The basic skills you need to train a dog are the same as those you need to train any other animal. One difference—and this is good news for you—is that (mainly due to our common history) there is no other animal as easy to train as a dog. On the other hand, there is a limit to how much you learn if you only train dogs.

Dogs forgive our mistakes and are nearly always motivated to cooperate. Other species scrutinize us far more thoroughly. We must earn their trust—if they don’t trust us, they won’t cooperate with us. A horse will not follow you if it doesn’t trust you, and it takes a lot to earn the trust of a horse (and only a moment to lose it). You can offer as many carrots as you like, but if it decides you are not someone to be trusted, the best carrots in the world will be to no avail. A cat will blink, at least twice, at you and the treat you offer it before even considering moving in your direction. Then, if it deems your request reasonable, it may just indulge you—otherwise, no deal.

The guinea pig, a favorite prey of many predators, including humans, is social and fearful by nature. We don’t share a common evolutionary history with it, as we do with the dog. You won’t get anything for free. You’ll have to work to gain your guinea pig’s trust and show it that cooperating with you is profitable in both the short and the long term.

Training guinea pigs will teach you the theory of animal learning. You’ll have to be precise and follow the correct procedures to produce the desired behavior. You’ll explore the whole spectrum of operant conditioning, but you’ll be left gasping for more. You’ll find yourself desperately attempting to think like a guinea pig, thus entering the realm of ethology.

You can teach dogs many things without a proper plan. They are so active and eager to please that, sooner or later, they will do something you like, which you can reinforce. With dogs, you can play by ear and sing along, but with other animals, you’ll need to plan. Timing is essential when you train your dog, but surprisingly enough, you’ll still achieve acceptable results even if your timing is off. With dogs, it’s like singing a melody out of tune and your friends still recognizing it. With guinea pigs, you’d better sing in tune, or they will tacitly suggest you get your act together before going back to them. It’s tough, but it’s also a good lesson about life.

Much like horses, guinea pigs tend to react fearfully when in doubt (a trait that has helped them survive throughout their evolutionary history). Displaying composed, self-confident behavior works well, but anything more assertive than that will backfire on you. Dogs, these ever amazing animals, give you a second chance (and understand our bad “accents” in dog language); a horse or a guinea pig hardly ever do so. If you even think of trying to bully a guinea pig into doing what you want, it will probably freeze for up to 30 minutes, which is a real stopper for any aspiring trainer.

You’ll learn soon enough that coercion is not the way to go at all. Thus, you’ll learn the secrets of motivation and the beauty of working within and with your environment, rather than attempting to control it, and that in itself will lead you to unexpected and welcomed results.

If they could, I’m sure your dog and your horse would thank the guinea pigs for what they teach you when you train them, for you become, undoubtedly, a much more subtle and balanced trainer. You’ll be in control of yourself rather than the animal, motivating rather than forcing, showing the way rather than fumbling about, achieving results with the least (sometimes even imperceptible) amount of intrusion into your favorite animal’s normal behavior.

If you have a chance, give it a try. We can never learn too much, can we?

Featured image: Dog and guinea pig together. Training a guinea pig can make you a better dog trainer (photo letsbefriends.blogspot.com).