Natural selection favors behaviors that prolong the life of an animal and increase its chance of reproducing; over time, a particularly advantageous behavior spreads throughout the population. The disposition (genotype) to display a behavior is innate (otherwise the phenotype would not be subject to natural selection and evolution), although it requires maturation and/or reinforcement for the organism to be able to apply it successfully. Behavior is, thus, the product of a combination of innate dispositions and environmental factors. Some behaviors require little conditioning from the environment for the animal to display it while other behaviors requires more.

Behavior is the response of the system or organism to various stimuli, whether internal or external, conscious or subconscious, overt or covert, and voluntary or involuntary.

Behavior does not originate as a deliberate and well-thought strategy to control a stimulus. Initially, all behavior is probably just a reflex, a response following a particular anatomical or physiological reaction. Like all phenotypes, it happens by chance and evolves thereafter.

An organism can forget a behavior if it does not have the opportunity to display it for a period of a certain length, or the behavior can be extinguished if it is not reinforced for a period.

Evolution favors a systematic bias, which moves behavior away from maximization of utility and towards maximization of fitness.

Social behavior is behavior involving more than one individual with the primary function of establishing, maintaining, or changing a relationship between individuals, or in a group (society).

Most researchers define social behavior as the behavior shown by members of the same species in a given interaction. This excludes behavior such as predation, which involves members of different species. On the other hand, it seems to allow for the inclusion of everything else such as communication behavior, parental behavior, sexual behavior, and even agonistic behavior.

Sociologists insist that behavior is an activity devoid of social meaning or social context, in contrast to social behavior, which has both. However, this definition does not help us much because all above mentioned behaviors do have a social meaning and a context unless ‘social’ means ‘involving the whole group’ (society) or ‘a number of its members.’ In that case, we should ask how many individuals are needed in an interaction to classify it as social. Are three enough? If so, then sexual behavior is not social behavior when practiced by two individuals, but becomes social when three or more are involved, which is not unusual in some species. We can use the same line of arguing for communication behavior, parental behavior, and agonistic behavior. It involves more than one individual and it affects the group (society), the smallest possible consisting of two individuals.

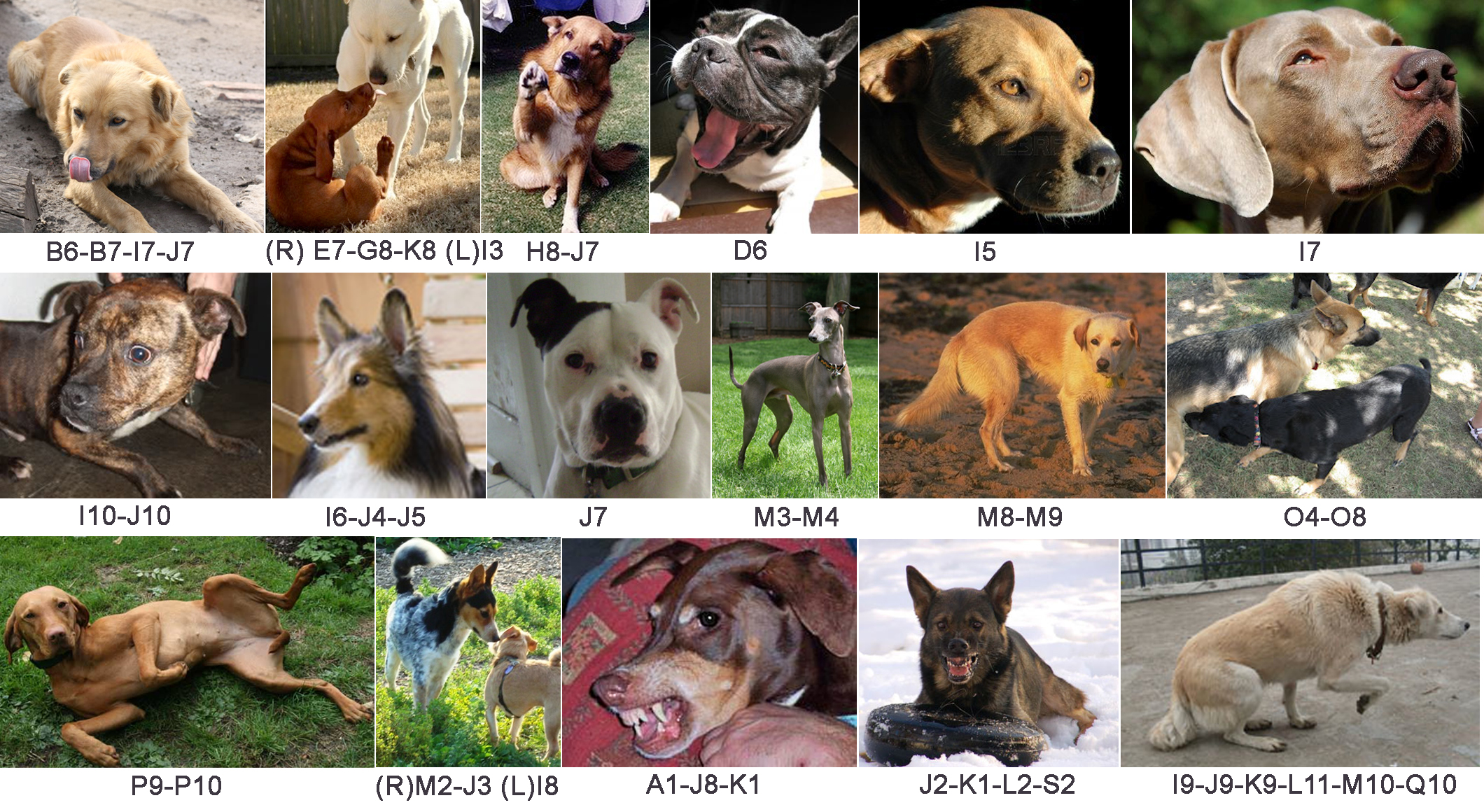

Agonistic behavior includes all forms of intraspecific behavior related to aggression, fear, threat, fight or flight, or interspecific when competing for resources. It explicitly includes behaviors such as dominant behavior, submissive behavior, flight, pacifying, and conciliation, which are functionally and physiologically interrelated with aggressive behavior, yet fall outside the narrow definition of aggressive behavior. It excludes predatory behavior.

Dominant behavior is a quantitative and quantifiable behavior displayed by an individual with the function of gaining or maintaining temporary access to a particular resource on a particular occasion, versus a particular opponent, without either party incurring injury. If any of the parties incur injury, then the behavior is aggressive and not dominant. Its quantitative characteristics range from slightly self-confident to overtly assertive.

Dominant behavior is situational, individual and resource related. One individual displaying dominant behavior in one specific situation does not necessarily show it on another occasion toward another individual, or toward the same individual in another situation.

Dominant behavior is particularly important for social animals that need to cohabit and cooperate to survive. Therefore, a social strategy evolved with the function of dealing with competition among mates, which caused the least disadvantages.

Aggressive behavior is behavior directed toward the elimination of competition while dominance, or social-aggressiveness, is behavior directed toward the elimination of competition from a mate.

Fearful behavior is behavior directed toward the elimination of an incoming threat.

Submissive behavior, or social-fear, is behavior directed toward the elimination of a social-threat from a mate, i.e. losing temporary access to a resource without incurring injury.

Resources are what an organism perceives as life necessities, e.g. food, mating partner, or a patch of territory. What an animal perceives to be its resources depends on both the species and the individual; it is the result of evolutionary processes and the history of the individual.

Mates are two or more animals that live closely together and depend on one another for survival.

Aliens are two or more animals that do not live close together and do not depend on one another for survival.

A threat is everything that may harm, inflict pain or injury, or decrease an individual’s chance of survival. A social-threat is everything that may cause the temporary loss of a resource and may cause submissive behavior or flight, without the submissive individual incurring injury. Animals show submissive behavior by means of various signals, visual, auditory, olfactory and/or tactile.

The diagram does not include a complete list of behaviors.

As always, have a great day!

R—

PS—I apologize if by chance I’ve used one of your pictures without giving you due credit. If this is the case, please e-mail me your name and picture info and I’ll rectify that right away.

Related articles

- Pacifying Behavior—Origin, Function and Evolution (aggression, dogs, dominance, evolution, pacifying, submission) 2012.06.06

- Muzzle Grab Behavior in Canids (dogs, wolf, behavior) 2012.04.25

- Dominance—Making Sense of the Nonsense (aggression, fear, dominance, submission, biology, behavior, wolfs, dogs, genetics, hierarchy, social) 2011.12.11

- The Magic Words “Yes’ And ‘No’ (dogs, training, language, punishment, SMAF) 2011.11.27

- Signal and Cue—What is the Difference? (signal, cue, dog, training, behavior) 2011.10.07

- Commands or Signals, Corrections or Punishers, Praise or Reinforcers (behavior, dog, training) 2011.10.03

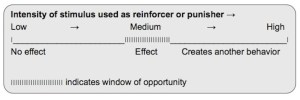

- Unveiling the Myth of Reinforcers and Punishers (behavior, behavior modification, reinforcers, punishers, operant conditioning) 2011.09.21

- The Spectrum of Behavior (behavior, aggression, fear, dominance, submission) 2011.09.09

- Magical Formula (behavior, evolution) 2011.09.04

References

- Abrantes, R. (1997) The Evolution of Canine Social Behavior. Wakan Tanka Publishers.

- Abrantes, R. (1997) Dog Language. Wakan Tanka Publishers.

- Case, L. P. (2005) The Dog: Its Behavior, Nutrition and Health. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Catania, A. C. (1997) Learning. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. 4th ed.

- Chance, P. (2008) Learning and Behavior.Wadsworth — Thomson Learning, Belmont, CA, 6th, ed.

- Coppinger, R. and Coppinger, L. (2001) Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. Scribner.

- Fentress, J. C., Ryon, J., McLeod, P. J., and Havkin, G. Z. (1987) A multi- dimensional approach to agonistic behavior in wolves. In Man and wolf: advances, issues, and problems in captive wolf research. Edited by H. Frank. Springer: 1 Edition.

- Fox, M. W. (1984) Behaviour of Wolves, Dogs, and Related Canids. Krieger Publishers Company.

- Futuyma, D. J. (1997) Evolutionary Biology. Sinauer Associates, Inc. 2nd ed. 2009.

- Lockwood, R. (1979) Dominance in wolves–useful construct or bad habit. In The Behavior and Ecology of Wolves. Edited by E. Klinghammer. Garland Press: 1st ed.

- Lorenz, K. (1963) Das sogenannte Böse. Zur Naturgeschichte der Agression. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, München. edition 1998.

- Lorenz, K. (1966) On Aggression. Mariner Books. edition 1974.

- Lorenz, K. (1986) Evolution and Modification of Behavior. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

- Lopez, B. H. (1978) Of Wolves and Men. J. M. Dent and Sons Limited.

- Martin, P. and Bateson, P. (2007) Measuring Behaviour: An introductory guide. Cambridge University Press. 3rd ed.

- Maynard Smith, J. and Harper, D. (2003) Animal signals. Oxford University Press, UK.

- McFarland, D. (1982) The Oxford Companion to Animal Behaviour. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- McFarland, D. (1998) Animal Behaviour. Benjamin Cummings. 3rd ed.

- Mech, L. D. (1981) The wolf: the ecology and behavior of an endangered species. University of Minnesota Press.

- Mech, L. D. (1988) The arctic wolf: living with the pack. Voyageur Press, Stillwater, Minn.

- Mech, L. D. (2000) Alpha status, dominance, and division of labor in wolf packs. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center.Mech,

- Mech, L. D., Adams, L. G., Meier, T. J., Burch, J. W., and Dale, B. W. (2003) The wolves of Denali. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- Mech. L. D. and Boitani, L. (2003) Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. University of Chicago Press.

- Searcy, W. A., and S. Nowicki (2005) The Evolution of Animal Communication: Reliability and Deception in Signaling Systems. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

- Tinbergen, N. (2006) Social Behavior in Animals. Agrobios India.

- Wilson, E. O. (1975) Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass (New Edition 2000)

- Wilson, E. O. (1993) The Diversity of Life. W. W. Norton & Co. Inc.Wilson, E. O. (1999) Consilience. Vintage.

- Zimen, E. (1975) Social dynamics of the wolf pack. In The wild canids: their systematics, behavioral ecology and evolution. Edited by M. W. Fox. Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., New York. pp. 336-368. (New Edition 2009)

- Zimen, Erik (1981) The Wolf: His Place in the Natural World. Souvenir Press.

- Zimen, E. (1983) A wolf pack sociogram. In Wolves of the world. Edited by F. H. Harrington, and P. C. Paquet. William Andrew.