“A reinforcer is not a reward.” Some things must be said again—and again.

For the umpteenth time, a reinforcer is not a reward. When I hear “Force-Free” trainers say, “dogs like to work to earn rewards,”1 I suspect and fear they miss by a mile and a half the essence and function of reinforcers in learning theory (and so also of inhibitors).

I’m not splitting hairs. There is a crucial difference between reinforcing a particular behavior and rewarding an individual. I suspect ignorance hereof is also the cause of the many incorrect statements on inhibitors2 from the “Radical Force-Free” camp (emphasis on radical).3

When terminology goes wrong

Look, I shouldn’t care less because reinforcers and the like are behaviorist things, and I’m an ethologist, not a behaviorist. But I do care, because my mind becomes strangely uneasy whenever I hear or see something fundamentally flawed and inconsistent.

If you claim the mantle of behaviorism, the least you can do is use its language correctly.

If you’re a behaviorist—and that’s what trainers in the “Radical Force-Free” camp are supposed to be—then at least be fair to the founding fathers of your learning philosophy and use the right terminology. All the rest seems to me an affront, disrespectful, and proof of unforgivable ignorance. Forgive the bluntness, but someone had to say it.

Back to the 1980s

“Dogs like to work to earn rewards” reminds me of the 1980s, when I opposed the old-school, military-style approach to dog training. The classes had all the charm of a drill parade: straight lines, sharp commands, leash jerks, and very little interest in what the dogs themselves thought of the matter—or whether they understood what we wanted of them. After ten minutes of marching back and forth, the instructor would say:

“And halt! Now, praise your dogs.”

Yes, I went to that kind of dog training with the first dog I had as an adult. That was the training we had back then.

I walked out in disgust with the sort of calm determination only youthful indignation can fuel. I decided there and then that Petrine, my dog, and I would train on our own and show them. We did.

Discovering training through ethology

I substituted praise with reinforcers—the real thing, not rewards—including my dygtig⁴ and a few treats given at strategic times and points. I stopped using a leash and started using a lead. Again, not splitting hairs—it makes a huge difference what you think of, and how you use, that piece of rope or leather that connects you to your dog.

A leash leashes; a lead leads. It’s as simple as that.

Leash jerks gave way to “No,” immediately followed by “dygtig,” when Petrine, not me, corrected the mistake. She seemed almost pleased to catch her own slips, as if this strange little team sport of ours finally made sense. She visibly enjoyed being my “teammate,” a role she took with disarming seriousness.

Learning from the giants

I was, then, a student of ethology, and I knew about social animals and social canines, including our domestic dog, and how contact, social acceptance, and feeling safe functioned as unconditioned, primary reinforcers (‘benefits of group living’ in ethology jargon). The social canines were among my favorites; I studied them diligently, inspired by my fellow senior students: Eberhard Trumler, Erich Klinghammer, Thomas Althaus, and Erik Zimen—alas, all gone now.

Old, venerable Professor Lorenz’s words rang in our ears by then (they still do):

“To understand an animal, first you have to become a partner.”

And so I did, applying to my training the best principles of ethology that I had learned from the great teachers—Lorenz, Tinbergen, von Frisch—and from my prominent elder colleagues. Later, I would even incorporate selected elements of behaviorism into what eventually became Animal Training My Way, but that is another story for another time.

Winning where no one expected us to

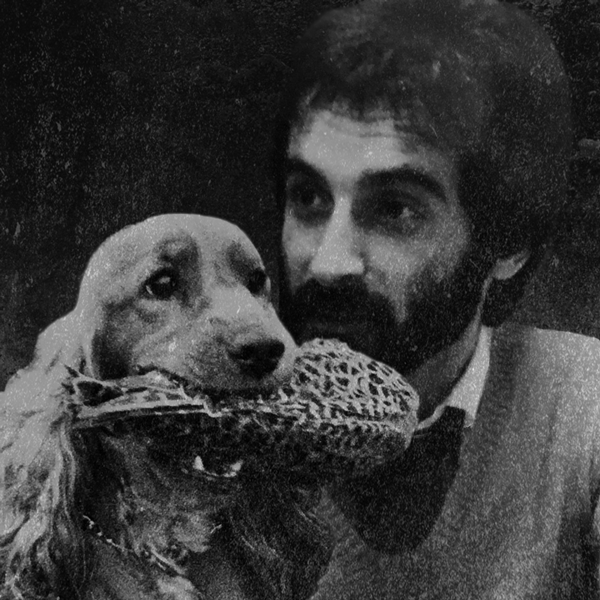

At the end of the term, I signed up for the final “obedience” competition at the club, a hunting dog club run by real green-clad hunters, and we won with max points. That a young long-haired fellow in faded Levi’s and clogs had won created some agitation—and to add insult to injury, my dog was a little, red, seven-month-old English Cocker Spaniel (a genuine one, not one of those oddballs we see in the US today), female on top of all.

Petrine was intelligent, beautiful, charming, a workaholic, and a sweetie-pie—though I suppose I was already helplessly devoted to her.

Our performance raised eyebrows and drew more humming than the establishment would have wished. At the prizes-and-punch social function, a few civilians asked me in a whisper whether I would help train their fidos (read: companion dogs).

And just like that, I was in deeper than I thought

The following Saturday, we were training on a grassy field across the road from where I lived, which is now the local firemen’s station. That was 1982, the summer before my son Daniel was born, and that’s how dog training came into my life. I never planned it.

Two years later, in 1984, I wrote my first book, Psychology Rather than Force, with far too little experience but loads of good ideas, including force-free, hands-free, reinforcement-based training—alas, all terms used as slogans these days—with as few inhibitors as possible; and it even included a whistle (the precursor of the clicker).

I was positive dog training would change. It did, and the rest is history.

And if this story has a punch line, it is this: reinforcers do the work—rewards are just the icing.

Notes

- This is an actual quote from a document published online by a confessed “Force-Free” trainer.

Note that Skinner writes about reinforcers and rewards, “The strengthening effect is missed, by the way, when reinforcers are called rewards. People are rewarded, but behavior is reinforced. If, as you walk along the street, you look down and find some money, and if money is reinforcing, you will tend to look down again for some time, but we should not say that you were rewarded for looking down. As the history of the word shows, reward implies compensation, something that offsets a sacrifice or loss, if only the expenditure of effort. We give heroes medals, students degrees, and famous people prizes, but those rewards are not directly contingent on what they have done, and it is generally felt that the rewards would not be deserved if they had been worked for” (Skinner, 1986, p. 569). ↩︎ - In 2013, I suggested we change punisher and derivatives to inhibitor and derivatives to avoid the moral and religious connotations of the former, particularly in Latin languages, and to emphasize their function and use as a learning tool. ↩︎

- “Radical Force-Free dog trainers” is my denomination for those trainers adhering to the positive or force-free movement, but having extreme views like claiming positive reinforcers are the only learning tool one needs, they never use aversive stimuli, one should never say “no,” everyone else but them is wrong, and other absurdities. Please do not confuse with the non-radical positive, force-free dog trainers who are equally force-free but sensible, open-minded, prudent in their claims, and polite and considerate to other thinkers. ↩︎

Reference List (First Editions in Original Language)

A tribute to my great teachers and senior fellow students:

Althaus, T. (1982). Verhaltensontogenese beim Siberian Husky [Dissertation, Universität Bern]. Institut für Zoologie.

Klinghammer, E. (Hrsg.). (1979). The behavior and ecology of wolves. Garland STPM Press.

(Original language: English; this edited volume was first published in English.)

Lorenz, K. (1949). Er redete mit dem Vieh, den Vögeln und den Fischen. Borotha-Schoeler.

(First German edition; this is the original form of what later became known in English as King Solomon’s Ring.)

Tinbergen, N. (1948). De natuur van het dier. Het Spectrum.

(First Dutch edition; predates the 1951 English The Study of Instinct.)

Trumler, E. (1961). Der Hund. Georg Müller Verlag.

(His earliest and most influential dog-ethology book; later expanded works followed.)

von Frisch, K. (1927). Aus dem Leben der Bienen. Springer.

(First German edition; foundational to his later Tanzsprache works.)

Zimen, E. (1971). Wolfsfibel. Kosmos Gesellschaft der Naturfreunde.

(Zimen’s first book-length publication in German; precedes later major works such as Der Wolf.)

References mentioned in the blog

Abrantes, R. (1984). Psykologi Fremfor Magt (Psychology Rather Than Force). Lupus Forlag.

Abrantes, R. (2015). Animal Training My Way. Wakan Tanka Publishers.

Abrantes. R. (2013). The 20 Principles All Animal Trainers Must Know. Wakan Tanka Publishers.

Skinner, B. F. 1986. What is wrong with daily life in the Western world? American Psychologist, 41(5), 568-574. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.5.568. Retrieved Jun. 29, 2019.

Featured photo: Roger Abrantes and Petrine in 1984 by Annemarie Abrantes.

📦 Glossary

Reinforcer

A consequence that increases the likelihood of a behavior being repeated.

In learning theory, a reinforcer is defined functionally, not emotionally: it works because it strengthens behavior, not because it feels like a “reward.”

Reward

A colloquial, subjective term for something the giver believes is pleasant to the recipient.

Unlike reinforcers, rewards do not have to change behavior—and often don’t.

This is why “reward” ≠ “reinforcer.”

Inhibitor

A consequence that reduces the likelihood that a behavior will recur.

The functional opposite of a reinforcer. Inhibitors are not “punishment” in the everyday sense—they can be as subtle as social disengagement or loss of access.

Dygtig (Danish)

Pronounced roughly “Dö-gtee.”

Literally “skilled” or “good,” introduced as a conditioned (or semi-conditioned) reinforcer in training (Abrantes, 1984). The “dygtig,” delivered with timing and consistency, and a friendly facial expression/body language, signals to the dog: “That was correct—keep doing it.” It embodies applied ethology at its best.

Lead vs. Leash

Lead: A tool intended to guide the dog; used with communication in mind.

Leash: A tool that often defaults to restraint.

The distinction reflects mindset more than equipment—a leash leashes; a lead leads.

Force-Free (in practice)

A training approach aiming to avoid aversive physical force.

Initially grounded in learning theory, but currently used in ways that often blur terminology and introduce inconsistencies between science and practice.

Primary Reinforcer

A stimulus that is naturally reinforcing without learning (conditioning)—for example, food, social contact, safety, and touch (in most circumstances).

Conditioned Reinforcer

A neutral stimulus (e.g., dygtig, a whistle, a click) that becomes reinforcing through association with a primary reinforcer.