—A Sniffer Dog is a Happy Dog

Scent detection has fascinated me since my early days as a student of biology, and I was already training detection animals at the beginning of the 1980s. Over the years, I have trained dogs, rats, and guinea pigs to detect narcotics, explosives, blood, vinyl, fungus, landmines, tuberculosis, and tobacco—and they excelled in all these tasks.

What has always intrigued me most is how deeply scent detection seems to be woven into their very being, regardless of species. Indeed, much before dogs became our partners in scent detection, olfaction had already shaped the mammalian brain—including ours. Although humans are often described as “microsmatic,” this view stems mainly from a 19th-century anthropocentric bias. In fact, human olfactory performance—when properly measured—can rival that of many other mammals (McGann, 2017). Fossil endocasts reveal that early mammalia forms possessed disproportionately large olfactory bulbs, suggesting that life for our distant ancestors was guided above all by smell (Rowe, Macrini, & Luo, 2011). The olfactory pathways remain among the most conserved in the mammalian nervous system, closely intertwined with limbic and reproductive circuits (Shipley & Ennis, 1996; Boehm, Zou, & Buck, 2005). As Lledo, Gheusi, and Vincent (2005) observed, “It is clear today that olfaction is a synthetic sense par excellence. It enables pattern learning, storage, recognition, tracking, or localization and attaches emotional and hedonic valence to these patterns” (p. 309). To smell, then, is not merely to detect—it is to think, feel, and remember.

Most of my detection work was carried out for the police, armed forces, SAR teams, or other professional agencies. Yet, I had written about scent detection already in the early 1980s, in my first book, Psychology rather than Force, published in Danish. Back in 1984, I called it “nose work” (a direct translation from the Danish næsearbejde). I recommended that all dog owners stimulate their dogs by giving them detection tasks, beginning with their daily rations. We even conducted some research on this, and the results were highly positive: dogs trained in detection work improved in many aspects of their otherwise problematic behavior. My recommendation remains the same today. Physical exercise is, of course, essential—but do not forget to stimulate your dog’s nose as well, perhaps its primary channel of information about the world.

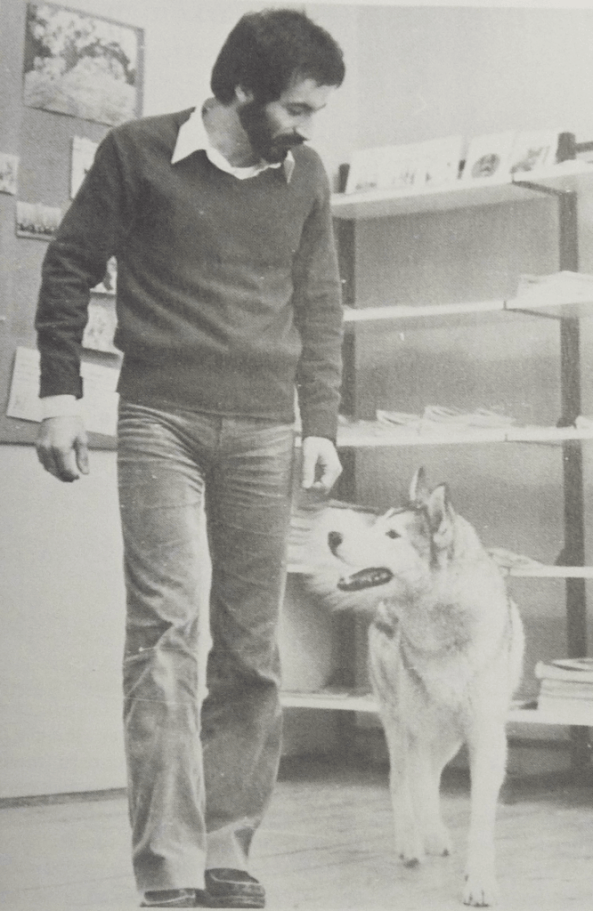

Above: In “Hundesprog” (Dog Language) from 1987, I mention “nose work” with an illustration from Alce Rasmussen. To the right: Yours truly in 1984 with a Siberian Husky, an “untrainable” dog, as everybody used to say. This was when my book “Psychology rather than Force” created a stir. We were then right at the beginning of the animal training revolution. In that book, I mention “nose work” (a direct translation from the Danish “næsearbejde”) and recommend it as an excellent way to stimulate our dogs.

Recent field data illustrate how central olfaction is to the daily lives of canids. Wolves in the Białowieża Forest, for instance, were active on average 45.2 % of every 24 hours—about 10.8 h per day—primarily in movement, travelling, and search behaviours (Theuerkauf et al., 2003, Table 1, p. 247). Monthly patterns (Figure 6, p. 249) suggest that activity levels vary with season, although exact numerical ranges are not provided in the text. Comparable patterns appear in other canids: red foxes spend about 43 % of their observable foraging time sniffing the ground (Wooster et al., 2019), and free-ranging domestic dogs devote substantial portions of their active time to exploratory and searching behaviours—activities guided predominantly by olfaction (Banerjee & Bhadra, 2022). These figures reveal that for a wolf or fox, using the nose is not an occasional act but a continuous occupation, consuming many hours each day.

| Measurement | % | Hours (h) |

|---|---|---|

| Time active | 45.2 % | 10.8 |

| Time moving | 35.9 % | 8.6 |

Table 1. Average daily activity of wolves in the Białowieża Forest, Poland (1994–1999), showing the proportion of time spent active and moving, both as a percentage of the 24-hour day and in hours. Data from Theuerkauf et al. (2003, Table 1, p. 247).

Note. “Time active” includes periods when wolves were travelling, hunting, or otherwise moving. Observations indicate that these behaviours are predominantly guided by olfaction. Activity was generally higher at night, and seasonal variation appears linked to day length and prey availability. On average, wolves were active roughly half the day (~10.8 h), highlighting that extensive daily searching and tracking is a defining feature of their ecology (Theuerkauf et al., 2003, Table 1, p. 247).

When I began promoting “nose work” in the early 1980s, I did so from personal experience rather than data. I spent many hours on scent detection with my English Cocker Spaniels. They loved it and were calmer, more focused, and more fulfilled than their peers who were not as nose-stimulated. I quickly discovered that scent detection was so self-reinforcing—in behaviorist terms—that no other reinforcers were needed beyond my approval, which they actively sought. In those moments, I realised that to be a dog is to be a cooperative nose-worker.

Science has since validated that intuition. Scent work is not a modern invention—it is a structured expression of what canids have done for thousands of years: exploring their world through odor cues. When we engage a dog’s nose, we are not merely training a skill; we are restoring a function at the very core of its evolution. Understanding that is perhaps the greatest lesson of scent detection: to educate and enrich a dog’s life, we must first respect the sensory world in which it truly lives.

References

Banerjee, A., & Bhadra, A. (2022). Time–activity budget of urban-adapted free-ranging dogs. Acta Ethologica, 25(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10211-021-00379-6

Boehm, U., Zou, Z., & Buck, L. B. (2005). Feedback loops link odor and pheromone signaling with reproduction. Cell, 123(4), 683–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.027

McGann, J. P. (2017). Poor human olfaction is a 19th-century myth. Science, 356(6338), eaam7263. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam7263

Lledo, P.-M., Gheusi, G., & Vincent, J.-D. (2005). Information processing in the mammalian olfactory system. Physiological Reviews, 85(1), 281–317. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00008.2004

Rowe, T. B., Macrini, T. E., & Luo, Z.-X. (2011). Fossil evidence on origin of the mammalian brain. Science, 332(6032), 955–957. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1203117

Shipley, M. T., & Ennis, M. (1996). Functional organization of olfactory system. Journal of Neurobiology, 30(1), 123–176. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199605)30:1%3C123::AID-NEU11%3E3.0.CO;2-N

Theuerkauf, J., Kamler, J. F., & Jedrzejewski, W. (2003). Daily patterns and duration of wolf activity in the Białowieża Forest, Poland. Journal of Mammalogy, 84(1), 243–253. https://ibs.bialowieza.pl/publications/1396.pdf

Wooster, E., Wallach, A. D., & Ramp, D. (2019). The Wily and Courageous Red Fox: Behavioural analysis of a mesopredator at resource points shared by an apex predator. Animals, 9(11), 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9110907

Featured image: Springer Spaniel, nose down, focused on a search.

Note: This article is a substantially revised and edited version of an earlier article from May 6, 2014, entitled Do You Like Canine Scent Detection? The revisions are extensive enough that the article deserves a new title and is therefore republished as new.