Cutting off parts of the body of an animal for our vanity is and will always be wrong for me independently of what science may discover.

Whether something is morally right or wrong depends on what you and I or anyone thinks, and it is not imposed on us by any scientific discovery. We need to distinguish between science and morality, between descriptive and normative statements.

Science is a collection of coherent, useful and educated predictions. All science is reductionist and visionary in a sense, but that does not mean that all reductionism is equally useful or that all visions are equally valuable or that one far-out idea is as acceptable as any other.

Greedy reductionism is bound to fail because it attempts to explain too much with too little, classifying processes too crudely, overlooking relevant detail and missing pertinent evidence.

Science sets up rational, reasonable, credible, useful and helpful explanations based on empirical evidence, which is not connected per se. The connections happen via our scientific models, ultimately allowing us to make reliable and educated predictions. A scientist needs to have an imaginative mind to think the unthinkable, discover the unknown and formulate initially far-fetched, but testable, hypotheses that may provide new and unique insights. As Kierkegaard writes, “This, then, is the ultimate paradox of thought: to want to discover something that thought itself cannot think.”

Morality and science are two separate disciplines. I may not like the conclusions and implications of some scientific studies, I may even find their application immoral; yet, my job as a scientist is to report my findings objectively.

Stating a fact does not oblige me to adopt any particular moral stance. The way I feel about a fact is not constrained by what science tells me. It may influence me but, ultimately, my moral decision is independent of the scientific fact. Science tells me men and women are biologically different in some aspects, but it does not say whether or not they should be treated equally in the eyes of the law. Science tells me that evolution is a consequence of the algorithm “the survival of the fittest,” not whether or not I should help those that find it difficult to fit into their environment. Science informs me of the pros and cons of eating animal products, but it does not tell me whether it is right or wrong to be a vegetarian.

If you think that the safest is to base your moral stances on factual events, you are walking on moving sands (and, probably, committing a fallacious appeal to nature).

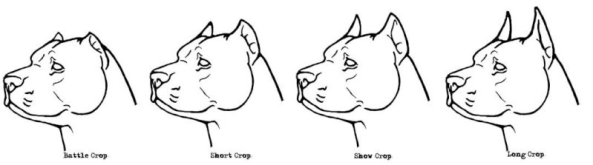

Let’s say someone asks you, “Why do you believe tail docking to be wrong?” If you answer, “Because it inhibits the dog to communicate adequately since dogs use their tails to communicate,” you are getting into trouble. Say again, the same person asks you, “Why do you believe ear cropping to be wrong?” You cannot answer, “Because it inhibits the dog to communicate adequately since dogs use their ears to communicate,” for upright ears allow the dogs to display more and easier detectable expressions than drop ears (though no study has proven that cropped ears are better to communicate than uncropped).

That is the hidden danger we run when using matters of fact to validate our moral statements: we may easily run into inconsistent argumentation. Even though seemingly that does not bother some, it certainly bothers me and other fellow thinkers with a certain degree of intellectual integrity.

You could avoid this problem by answering, ”Because I don’t like to cut off parts of an animal.” That would do it because nobody can argue with what you like or don’t like. Even if you neuter your male dog (which means cutting off the testicles of the animal), you are still off the hook because you can say, “I did it, and I don’t like it.” There is no logical contradiction in doing something without liking it. It is only logically contradictory if you infer the premise “we only do what we like.” “I don’t like diets and I’m on a diet” is perfectly all right. You may have a goal, which requires you to do things you don’t like.

Another aspect of this hidden danger of basing your morality on facts is that if science uncovers some new fact relevant to your morality, you’ll be compelled to change it. One moment right, the nest wrong applies to scientific theory, but not necessarily to morality.

For example, if I use the seemingly good argument, “for me, it is wrong to inflict unnecessary pain and distress to any living creature, independently of species,” my morality is at the mercy of scientific discovery.

Thus, the only way I can make my moral rule stick appears to be the subjective argument: for me, it is wrong to cut off parts of an animal’s body because I don’t like it. And if science uncovers some painless, undistressing procedures of docking and cropping, so be it. I still don’t like it and won’t do it. Period.

References

Ayer, A. J. (1936). Language, truth, and logic. Gollancz.

Churchman, C. W. (1961). Prediction and optimal decision. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Elqayam, S., & Evans, J. St. B. T. (2011). Descriptivism versus normativism in the study of human thinking. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34(5), 233–248.

Hume, D. (1739–1740). A treatise of human nature. (L. A. Selby-Bigge & P. H. Nidditch, Eds., 2nd ed., 1978). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1739–1740)

Quintelier, K., Van Speybroeck, L., and Braeckman, J. (2010). Normative ethics does not need a foundation: It needs more science. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine, 5, Article 5. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3068523/.

Moore, G. E. (1903). Principia ethica. Cambridge University Press.