Abstract

Stress is often portrayed as harmful, yet moderate, acute stress can enhance learning, memory retention, and social bonding. Recent epigenetic research reveals that stress hormones modulate gene expression in key brain regions, strengthening memory consolidation and attentional processes. Unpleasant or intense experiences tend to form long-lasting memories, an adaptive mechanism for survival. Beyond cognition, stress can facilitate social bonding through oxytocin-mediated social buffering, as demonstrated in mammals, including domesticated dogs, although effects are highly context-dependent. Excessive or chronic stress, however, disrupts these processes, impairing memory, social interactions, and overall well-being. This paper emphasizes the nuanced, dual role of stress, highlighting its adaptive functions and underscoring the importance of understanding stress within an evolutionary and behavioral framework, not least because such understanding can inform more efficient animal behavior modification.

Stress Helps Learning and Bonding

A tough nut to crack is an everlasting memory that binds the parties together, and there is a reason for that. Moderate stress heightens arousal and sharpens attention, facilitating learning and the formation of durable memories (Roozendaal, McEwen, & Chattarji, 2009; McGaugh, 2015). Studies show that stress-related hormones and neuromodulators can also strengthen certain social bonds, depending on context, species, and prior history (Carter, 2014; Hostinar, Sullivan, & Gunnar, 2014).

The Term Stress Is Dangerously Ambiguous

We need to be careful, though. The term stress is dangerously ambiguous. Richard Shweder once described stress in a 1997 New York Times, Week in Review essay, as “a word that is as useful as a Visa card and as satisfying as a Coke. It’s non-committal and also non-committable.” Here, we adopt a biological definition:

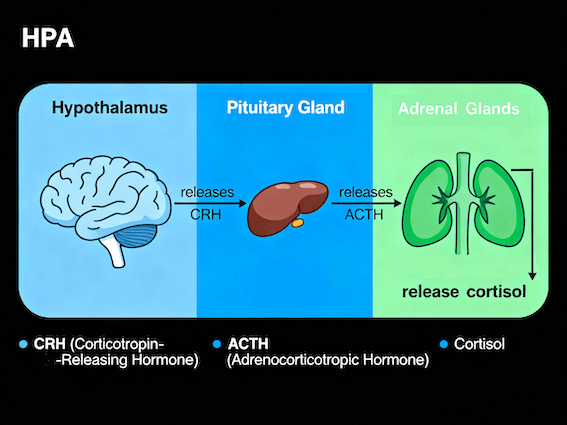

Stress is the organism’s coordinated physiological response to a real or perceived challenge to homeostasis, involving the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis to restore equilibrium (see fig. 1).

This distinction—between colloquial and biological uses—is crucial because the physiological and behavioral mechanisms engaged differ depending on whether the stressor is acute or chronic, controllable or uncontrollable. In this context, Koolhaas et al. (2011, p. 1291) propose that “the term ‘stress’ should be restricted to conditions where an environmental demand exceeds the natural regulatory capacity of an organism, in particular situations that include unpredictability and uncontrollability,” emphasizing the adaptive and context-dependent nature of the stress response (McEwen & Wingfield, 2010; Koolhaas et al., 2011).

What Is the Function of Stress?

Being an evolutionary biologist, when contemplating a mechanism, I always ask: “What is the function of that? What is that good for?” A mechanism can originate by chance (most do), but unless it provides the individual with some extra benefits in survival and reproduction, it will not spread in the population. From an evolutionary perspective, the stress response and the modulation of memory under stress increase the probability of survival (Nesse & Ellsworth, 2009; McEwen, Nasca, & Gray, 2016).

Why Do Unpleasant Memories Persist?

Emotionally intense, threatening, or highly arousing situations produce stronger, more persistent memory traces. Biologically, remembering potentially harmful events helps self-preservation. Negative or threatening events recruit the amygdala–hippocampal network more strongly, with the amygdala modulating hippocampal consolidation via noradrenergic and glucocorticoid-dependent mechanisms (Johansen, Cain, Ostroff, & LeDoux, 2011; McGaugh, 2015; LeDoux & Pine, 2016).

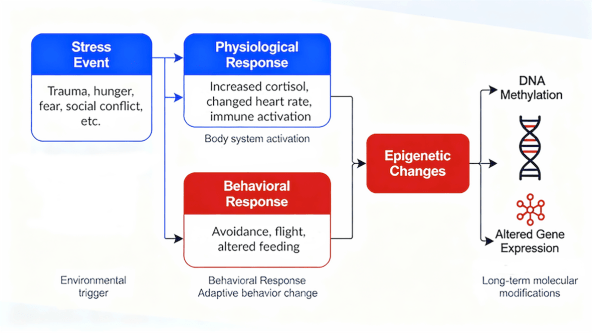

Epigenetic Effects

One of the most exciting scientific discoveries of late is the role of epigenetics (see fig. 2). Epigenetics—the study of modifications in gene activity that occur without altering the DNA sequence—has become central to contemporary models of learning and memory. Bird defines an epigenetic event as “the structural adaptation of chromosomal regions so as to register, signal or perpetuate altered activity states” (Bird, 2007, p. 398). Within this framework, attention focuses on activity-dependent chromatin modifications that occur during an individual’s lifetime rather than on transgenerational inheritance (Allis & Jenuwein, 2016). Mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone acetylation, and related chromatin adjustments fine-tune gene expression in response to salient experiences, enabling the formation and stabilization of memory (Sweatt, 2013). Stress hormones act on mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors in hippocampal and amygdalar circuits, where they modulate plasticity and enhance the consolidation of significant events (Roozendaal, McEwen, & Chattarji, 2009; McEwen et al., 2012). Through interactions with noradrenergic projections from the locus coeruleus, glucocorticoids further shape these epigenetic regulators, influencing transcriptional programs essential for synaptic plasticity (Zovkic, Guzman-Karlsson, & Sweatt, 2013; Gray, Rubin, Hunter, & McEwen, 2014). These coordinated molecular processes, under moderate stress, enhance learning and contribute to the durability of highly arousing or threatening experiences.

Not All Stress Boosts Learning

Not all stress is productive for learning. Excessive stress produces the opposite effect. There is a difference between being stressed and stressed out. When stress becomes excessive or prolonged, the organism enters a state where immediate survival takes priority over other functions, and memory formation decreases. Chronic stress, in particular, undermines learning and cognitive function by disrupting hippocampal structure and impairing synaptic plasticity (de Kloet, Joëls, & Holsboer, 2005). These maladaptive effects highlight that stress is beneficial only within a moderate and context-dependent range; beyond that, it impairs both cognition and emotional regulation.

Stress and Bonding—A Delicate Balance

Stress does more than enhance memory; under certain conditions, it actively promotes social bonding. Oxytocin, a neuropeptide closely linked to affiliation, mediates this effect by dampening the HPA axis response during shared or moderate stress, thereby encouraging proximity and affiliative behaviors (Crockford, Deschner, & Wittig, 2017). In rodents, moderate stress enhances social-seeking behavior among cagemates via oxytocin signaling, though excessively threatening contexts abolish this effect (Burkett et al., 2015). Findings in rodents provide a foundation for understanding oxytocin-mediated bonding, which can also be observed in humans and domesticated dogs, albeit with species-specific nuances.

In domesticated dogs, exogenous oxytocin increases sociability toward humans and conspecifics, and social interactions raise endogenous oxytocin levels (Nagasawa et al., 2015). Just as humans bond emotionally through mutual gaze—a process mediated by oxytocin—Nagasawa et al. demonstrate that a similar gaze-mediated bonding exists between humans and dogs: “These findings support the existence of an interspecies oxytocin-mediated positive loop facilitated and modulated by gazing, which may have supported the coevolution of human-dog bonding by engaging common modes of communicating social attachment” (Nagasawa et al., 2015, p. 333). Longitudinal observations further show that chronic stress markers, such as hair cortisol, can synchronize between dogs and their owners, suggesting a deep physiological linkage (Sundman et al., 2020). Importantly, these bonding effects are highly context-dependent: moderate, predictable stress tends to facilitate affiliation, whereas excessive or prolonged stress may inhibit social bonding.

Caveats: Despite the fascinating discoveries mentioned above, we must be prudent in our conclusions. The effects of stress on bonding are highly context-dependent. Elevated cortisol in dogs can reflect excitement rather than distress (Nagasawa et al., 2015), and the benefits observed in rodents require non-threatening environments (Burkett et al., 2015). Oxytocin’s influence varies with social familiarity; stress may not enhance affiliation with strangers or weakly bonded partners (Crockford et al., 2017). Correlational studies, such as cortisol synchronization in dog–owner dyads, cannot prove causality, though they suggest physiological coupling that may support bonding under shared stress.

Conclusion

We need a balanced view of stress. Acute, manageable challenges—those that elicit adaptive stress responses—support attentional sharpening, facilitate memory consolidation, strengthen social bonds, and promote effective learning. These benefits are highly context-dependent: stress can enhance cognition and affiliation when moderate and predictable, but excessive or prolonged stress can overwhelm these systems, impairing memory, social interactions, and overall well-being. From an evolutionary perspective, stress serves a dual adaptive function—preparing individuals to respond to threats while reinforcing social bonds that increase survival odds. A nuanced understanding is therefore essential for interpreting behavior and guiding sound practice.

For animal trainers, these insights translate into a few practical guidelines. Animals benefit from gradual exposure to manageable, stress-eliciting challenges that promote resilience and adaptive coping. Training sessions should be calibrated so that the stress elicited remains within a range that facilitates attention and learning—enough to trigger mild HPA-axis activation, but not so intense as to be counter-productive. Moreover, designing training sessions that employ an appropriate level of stress can strengthen the trainer–animal bond by allowing the trainer to serve as a social buffer during mildly stressful tasks.

Featured picture: A tough nut to crack is an everlasting memory that binds the parties together (photo by unknown).

References

Allis, C. D., & Jenuwein, T. (2016). The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17(8), 487–500. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.59

Bird, A. (2007). Perceptions of epigenetics. Nature, 447(7143), 396–398. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05913

Burkett, J. P., Andari, E., Johnson, Z. V., Curry, D. C., de Waal, F. B. M., & Young, L. J. (2016). Oxytocin‑dependent consolation behavior in rodents. Science, 351(6271), 375–378. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4785

Carter, C. S. (2014). Oxytocin pathways and the evolution of human behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115110

Crockford, C., Deschner, T., & Wittig, R. M. (2017). The role of oxytocin in social buffering of stress: What do primate studies add? Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 30, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2017_12

de Kloet, E. R., Joëls, M., & Holsboer, F. (2005). Stress and the brain: From adaptation to disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6(6), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1683

Gray, J. D., Rubin, T. G., Hunter, R. G., & McEwen, B. S. (2014). Hippocampal gene expression changes underlying stress sensitization and recovery. Molecular Psychiatry, 19(11), 1171–1178. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2013.175

Hostinar, C. E., Sullivan, R. M., & Gunnar, M. R. (2014). Psychobiological mechanisms underlying the social buffering of the stress response: A review of animal models and human studies across development. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 256–282. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032671

Hunter, R. G., & McEwen, B. S. (2013). Stress and anxiety across the lifespan: Structural and molecular correlates. Neuroscience, 255, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.09.039

Johansen, J. P., Cain, C. K., Ostroff, L. E., & LeDoux, J. E. (2011). Molecular mechanisms of fear learning and memory. Cell, 147(3), 509–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.009

Koolhaas, J. M., Bartolomucci, A., Buwalda, B., de Boer, S. F., Flügge, G., Korte, S. M., … Fuchs, E. (2011). Stress revisited: A critical evaluation of the stress concept. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(5), 1291–1301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.02.003

LeDoux, J. E., & Pine, D. S. (2016). Using neuroscience to help understand fear and anxiety: A two-system framework. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(11), 1083–1093. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16030353

McEwen, B. S., Eiland, L., Hunter, R. G., & Miller, M. M. (2012). Stress and anxiety: Structural plasticity and epigenetic regulation as a consequence of stress. Neuropharmacology, 62(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.07.014

McEwen, B. S., Nasca, C., & Gray, J. D. (2016). Stress effects on neuronal structure: Hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.171

McEwen, B. S., & Wingfield, J. C. (2010). What is in a name? Integrating homeostasis, allostasis, and stress. Hormones and Behavior, 57(2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.09.011

McGaugh, J. L. (2015). Consolidating memories. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-014954

Nagasawa, M., Mitsui, S., En, S., Ohtani, N., Ohta, M., Sakuma, Y., … Kikusui, T. (2015). Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human–dog bonds. Science, 348(6232), 333–336. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261022

Nesse, R. M., & Ellsworth, P. C. (2009). Evolution, emotions, and emotional disorders. American Psychologist, 64(2), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013503

Roozendaal, B., McEwen, B. S., & Chattarji, S. (2009). Stress, memory and the amygdala. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 423–433. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2651

Sundman, A.-S., Van Poucke, E., Svensson Holm, A.-C., Faresjö, Å., Theodorsson, E., Jensen, P., & Roth, L. S. V. (2020). Long-term stress levels are synchronized in dogs and their owners. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 17112. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74204-8

Sweatt, J. D. (2013). The emerging field of neuroepigenetics. Neuron, 80(3), 624–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.023

Zovkic, I. B., Guzman-Karlsson, M. C., & Sweatt, J. D. (2013). Epigenetic regulation of memory formation and maintenance. Learning & Memory, 20(2), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.026575.112