It dawned on me the other day, while at sea, one of those days with scattered clouds on the horizon and a fair wind barely sufficient to keep the boat sailing. Simplicity, that’s what makes it so soothing and scaringly beautiful. The sea invites you to dream, but make no promises; it is what it is, neither more or less. Be wise, and it will reward you; be foolish, and it will punish you.

You can’t hide at sea; you’ll encounter yourself whether you want it or not. The only viable strategy is honesty and integrity. It’s all so simple. The sea possesses this power, I discovered—the pertinent appears suddenly as frivolous, and the complex reveals itself in all its simple parts.

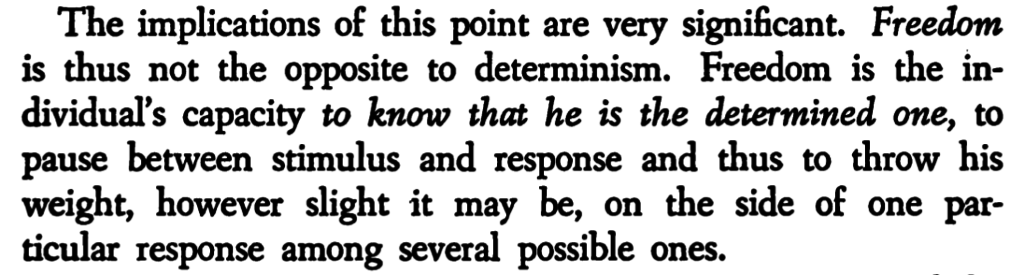

I felt absolutely ecstatic, like something major was happening, yet nothing particular stood out. As far as the eye could see, the world was an endless expense of blue, only slightly interrupted by a thin line, far, far away. Sea and sky, a few clouds on the horizon, the sun to the west, no birds, no fish, no sounds but the slight, rhythmic splashes of the boat gracefully cutting through the water, almost as silently as the flight of the owl.

Simplicity—I suppose, is what fascinates me most about Darwin’s brilliant concept of evolution by means of natural selection. The algorithm the survival of the fittest is the simplest idea one can conceive, and yet so powerful that it cuts through everything our understanding touches.

I have come to view the principle of simplicity as an old friend, always by my side as long as I can remember. From my young student days to the times of book writing or when on practical commissions, my friend Simplicity has been there, unobtrusively muttering, “Seek the simple…”

The principle of simplicity, as such, was first propounded by the English philosopher, William of Occam (1300-1349). We also know it as Occam’s Razor: “Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem,” which is Latin for “Entities should not be multiplied more than necessary,” or “If two assumptions seem to be equally valid, the simpler one should be preferred.”

Simple is beautiful and simpler is beautifuller—and the sea has this influence on you. Thus, I took the liberty to apply the principle of simplicity to its own definition, and three corollaries emerged.

“If you have more than one option, choose the simplest.”

- First corollary: “If you have only one option, you don’t have a problem; don’t waste your time complaining, just accept it and keep smiling!”

- Second corollary: “If you don’t like having only one option, work to create more; then you’ll have the problem of choosing one.”

- Third corollary: “If you don’t like having problems, don’t create options.” Return, then, to the first corollary, don’t complain, and keep smiling!

And so it is that I continue sailing across this vast sea of blue, feeling my heart beating for every, ever-so-gentle splash of the hull against the water. It all seems so simple: I am just a little ripple in the immense ocean, yet I am alive, and hence I must embrace life fully for as long as I can.

________________

Featured image: A few clouds on the horizon and a fair wind, barely enough to keep the boat sailing.

Note: This blog is an updated version of the original post “I’m Alive and I Have Only One Option” published on April 21, 2014. I made minor adjustments to the language to better convey my thoughts, for I had struggled with a few sentences in the original. The text is now more to my liking; however, upon re-reading it, I noticed a slight but significant change in its undertone, which is why I felt it deserved a new title. And yes, I kept the term “beautifuller.” It’s archaic from the 1800s, I know, but since I’m getting pretty archaic myself, I feel it’s fitting.

References

McFadden, J. (2023). Razor sharp: The role of Occam’s razor in science. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.15086 (PMC article: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10952609/).

Walsh, D. (1979). Occam’s razor: A principle of intellectual elegance. American Philosophical Quarterly, 16(3), 241–244. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20009764.

Your comments are welcome. Please feel free to leave a reply.